Buzan, Barry and Lawson, George (2013) The global transformation: the nineteenth century and the making of modern international relations. International Studies Quarterly, 57 (3). pp. 620-634. ISSN 0020-8833. © 2012 International Studies Association.

LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research.

.~`~.

The Global Transformation:

The Nineteenth Century and the Making of Modern International Relations

Unlike many other social sciences, International Relations (IR) spends relatively little time assessing the impact of the 19th century on its principal subject matter. As a result, the discipline fails to understand the ways in which a dramatic reconfiguration of power during the ‘long 19th century’ served to recast core features of international order. This paper examines the extent of this lacuna and establishes the ways in which processes of industrialization, rational state-building, and ideologies of progress served to destabilize existing forms of order and promote novel institutional formations. The changing character of organized violence is used to illustrate these changes. The paper concludes by examining how IR could be rearticulated around a more pronounced engagement with ‘the global transformation’.

This article examines the lack of attention paid by International Relations (IR) scholarship to the 19th century and argues that this shortcoming sets the discipline on tenuous foundations. A number of core themes in the discipline – from issues of sovereignty and inequality to broader dynamics of political economy, state interactions, and military relations – have their roots in 19th century transformations. Indeed, it could be argued that the current benchmark dates around which IR is organized – 1500 (the opening of the sea lanes from Europe to the Americas and the Indian Ocean), 1648 (the emergence of modern ‘Westphalian’ notions of sovereignty), 1919 and 1945 (the two World Wars and start of the Cold War as major contestations over world power), and 1989 (the end of the Cold War and bipolarity) – omit the principal dynamics that established the modern international order (Buzan and Lawson 2013). These commonly held ‘turning points’ are not so much wrong as misleading. They emphasize the distribution of power without focusing on underlying modes of power, and they focus on the impact of wars without examining the social developments that gave rise to them. Once the magnitude of the changes initiated during the 19th century is recognized, it becomes clear that we are not living in a world where the principal dynamics are defined by the outcomes of 1500, 1648, 1919, 1945, or 1989. We are living now, and are likely to be living for some time yet, in a world defined predominantly by the downstream consequences of the 19th century. If IR is to gain a better grasp of its core areas of enquiry, the global transformation of the 19th century needs to become more central to its field of vision.

It is not our claim that all IR scholarship ignores the 19th century – it is relatively easy to find work that refers to the Concert of Europe or to the rise of the firm, and which interrogates the thought of 19th century figures such as Clausewitz, Marx, and Nietzsche. Rather, our intervention is motivated by the failure of IR to understand the 19th century as home to a ‘global transformation’ which radically reshaped domestic societies and international order. For most sociologists and economic historians, the 19th century global transformation – often shorthanded as modernity – provides the basic foundations of their disciplines. This is not the case in IR. We interrogate the reasons for this lacuna and establish why this gap creates difficulties for understanding the emergence and institutionalization of modern international order. Our argument is first, that a set of dynamics established during the 19th century intertwined in a powerful configuration that reshaped the social bases of international order; and second, that this configuration continues to serve as the underpinning for much of contemporary international relations.

There are four background assumptions that lie behind our claims.

First, by ‘the 19th century’, we do not mean the standard IR designation of 1815-1914. We include some aspects of modernity that were established during the late 18th century, but which matured principally in the 19th century (such as industrialization), and we follow some dynamics through to the early decades of the 20th century (such as changes in the organization of violence). Our understanding shares affinities to Eric Hobsbawm’s (1987: 8) concept of ‘the long 19th century’, sandwiched between the ‘Atlantic Revolutions’ of America, France, and Haiti on the one hand, and World War I on the other. We show how much of IR’s contemporary agenda stems from cumulating transformational changes during this period, and what benefits would accrue to IR from making these transformations more prominent in its enquiries.

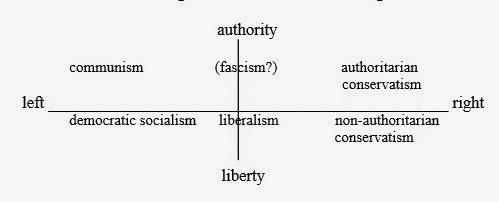

Second, we are aware of the dangers which stem from claims that modernity was a uniquely European development arising from endogenous civilizational qualities (e.g. Jones 1981; Landes 1998; North et al 2009). We do not subscribe to this view. Rather, we recognize that many of the processes that generated the historically specific configuration of ‘global modernity’ originated outside Europe (Goody 1996; Wolf 1997; Frank 1998; Pomeranz 2000; Bayly 2004; Hobson 2004; Darwin 2007). European development was asynchronous and interactive, produced by the ‘promiscuous interconnections’ of people, institutions, and practices (Bayly 2004: 5; Hobson 2004: 304). For example, British development relied on its position as the imperial centre of an Atlantic economy nurtured by the raw materials wrought from coercive practices such as slavery, indentured labor, and the plantation system (Gilroy 1993: 2; Blackburn 1997: 510, 530, 581; Frank 1998: 277-8). Our aim, therefore, is not to replicate, let alone reinforce, Eurocentric accounts of ‘the European miracle’ (Jones 1981). Rather, our emphasis is on the intertwined configuration of industrialization, rational state building, and ideologies of progress which, co-constituted by external and internal processes, cohered in parts of north-western Europe towards the end of the 18th century. By industrialization we mean both the commercialization of agriculture and the two-stage industrial revolution, which generated an intensely connected global market. As we point out below, the extension of the market brought new opportunities for accumulating power, not least because of the close relationship between industrialization, dispossession, and exploitation. Indeed, industrialization in some states (such as Britain) was deeply interwoven with the forceful de-industrialization of others (such as India). By rational state-building, we mean the process by which many administrative and bureaucratic competences were ‘caged’ within national territories. This process was not pristine: processes of imperialism and state-building were co-implicated. Finally, by ‘ideologies of progress’, we mean symbolic schemas such as modern liberalism, socialism, and nationalism which were rooted in ideals of progress and, in particular, associated with Enlightenment notions of improvement and control. Once again, there was a dark side to these ideologies – the promise of progress was closely linked to a ‘standard of civilization’ which served as the legitimating currency for coercive practices against ‘barbarian’ outsiders (Keene 2002; Anghie 2004; Suzuki 2005). These institutional formations worked together to foster a substantial power gap between a few European states and the rest of the world. By the end of the 19th century, four states (Britain, France, Germany, and the United States) provided two-thirds of the world’s industrial production. And one of these powers, Britain, became the first global superpower, counting a quarter of the world’s inhabitants as its subjects, while claiming a similar proportion of its territory (Sassen 2006: 74).

Third, it is important to note that not everything changed during the 19th century: agriculture and non-carbon based production remained an important component of most economies, including in Europe where, with the exception of Britain, even in 1900 between one-quarter (e.g. Holland) and two-thirds (e.g. Italy) of the population worked on the land (Blanning 2000: 3, 97). Empires remained important sites of political authority up to, and beyond, the onset of World War I (Burbank and Cooper 2010: 20-1). And many social hierarchies proved resilient – the nobility, gentry, and landholding classes remained influential everywhere (Tombs 2000: 30-1; Bayly 2004: 451). Given this, modernity should not be seen as a singular moment of sharp discontinuity, but as a protracted, uneven process (Teschke 2003: 43, 265). However, even if there is no hard-and-fast dichotomy between modern and pre-modern eras, it is possible to speak of a basic epochal disjuncture in that, during the 19th century, a concatenation of changes set in place a range of profoundly transformative processes. These changes coalesced first in a small core of states from where both their effect (a revolutionary configuration in the mode of power) and their challenge (how other societies responded to this configuration) spread rapidly. These issues still define the basic structure of international relations and many of its principal issues.

Fourth, the analytical narrative we sustain argues that global modernity can be characterized by the intensification of differential development and heightened interactions between societies. In other words, different experiences of the configuration we highlight were accentuated by increasingly dense connections between societies. The result was ‘differential integration’ into global modernity (Halliday 2002). Intensified trade, improved transport and communication systems, and practices such as colonialism generated a denser, more integrated international system. As a consequence, levels of interdependence rose, making societies more exposed to developments elsewhere. However, during the 19th century, the development gap between societies opened more widely than ever before. Unevenness has always been a basic fact of historical development (Rosenberg 2010), but never was unevenness felt on this scale, with this intensity, or in a context of such close, inescapable interdependence. Those with machine guns, medicine, industrial power, railroads, and new forms of bureaucratic organization gained a pronounced advantage over those with limited access to these sources of power. The resulting inequalities fostered the emergence of a hierarchical international order, the establishment of which defines the basic commonality between the 19th century and the contemporary world.

Our argument unfolds in four parts. First, we evaluate the limited ways in which IR scholarship approaches the 19th century. Second, we establish an understanding of the 19th century as home to a ‘global transformation’ – an intertwined configuration of industrialization, rational state building, and ideologies of progress. Third, we illustrate the potency of this configuration by examining the ways in which a transformation of the means of organized violence, along with a comparable intensification of interactions between societies, produced the hierarchical international structure which continues to undergird core aspects of contemporary international relations. We conclude by considering the ways in which IR can be rearticulated through deeper appreciation of this ‘global transformation’.

.~`~.

IR and the 19th Century

There are four main ways in which IR approaches the 19th century: as an absence; as a point of data accumulation; as a fragment of a wider research program; and within Eurocentric accounts of the expansion of international society. This section briefly assesses these four approaches.

Perhaps the main IR approach to the 19th century is to ignore it. The 1648 Treaty of Westphalia is considered by most to be the intellectual basis for the discipline, establishing a ‘revolution in sovereignty’ that is taken to be a ‘historical faultline’ in the formation of modern international order (Philpott 2001: 30, 77). Constructivists, in particular, see Westphalia as marking a fundamental shift from feudal heteronomy to modern sovereign rule through the emergence of principles of exclusive territoriality, non-intervention, and legal equality (e.g. Ruggie 1983: 271-9). However, Westphalia is also given prominent attention by realists (e.g. Morgenthau 1978), English School theorists (e.g. Watson 1992), and liberal cosmopolitans (e.g. Held et al. 1999).

Regardless of the cross-paradigmatic hold of Westphalia, its centrality to the formation of modern international order is questionable. Most obviously, Westphalia did not fundamentally alter the ground-rules of European international order. Neither sovereignty, non-intervention, nor the principle of cuius regio, eius religio were mentioned in the Treaty (Osiander 2001: 266; Carvalho et al 2011: 740). Rather, Westphalia was part of a long-running battle for the leadership of dynastic European Christianity – its main concerns were to safeguard the internal affairs of the Holy Roman Empire and to reward the victors of the Wars of Religion (France and Sweden) (Osiander 2001: 266). Indeed, Westphalia set limits to the idea of sovereignty established at the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, for example by retracting the rights of polities to choose their own confession. Westphalia decreed that each territory would retain the religion it held on 1st January 1624 (Teschke 2003: 241; Carvalho et al 2011: 740). More generally, Westphalia did not lead to the development of sovereignty in a modern sense – European order after 1648 remained a ‘patchwork’ of marriage, inheritance, and hereditary claims rather than constituting a formal states system (Osiander 2001: 278; Teschke 2003: 217; Nexon 2009: 265). It is unsurprising, therefore, to find imperial rivalries, hereditary succession, and religious conflicts at the heart of European wars over subsequent centuries. Although German principalities assumed more control over their own affairs after 1648, this was within a dual constitutional structure which stressed loyalty to the Empire (reichstreue) and which was sustained by a court system in which imperial courts adjudicated over both interstate disputes and internal affairs (Teschke 2003: 242-3). Overall, Westphalia was less a ‘watershed’ than an affirmation of existing practices, including the centrality of imperial confederation, dynastic order, and patrimonial rule (Nexon 2009: 278-80).

Much IR scholarship jumps from the intellectual ‘big bang’ of Westphalia to the establishment of IR as a discipline after World War I (Carvalho et al. 2011: 749). However, the equation of the First World War with the institutionalization of IR as a discipline is equally problematic. First, it occludes the fact that international thought became increasingly systematic during the last part of the 19th century, being taught in some US Political Science departments (such as Columbia) and fuelling major debates about international law, imperialism, geopolitics, trade, and war in both Europe and the United States (Knutsen 1997; Schmidt 1998; Carvalho et al. 2011: 749; Hobson 2012). IR, therefore, did not spring de novo in 1919, but has a longer genealogy formed in the unprecedented environment of global modernity during the late 19th century. Second, standard accounts tend to omit the closeness of the links between IR, colonial administration, and racism (Bell 2007; Vucetic 2010; Hobson 2012). IR’s early concerns were forged within Anglo-American epistemic communities which imagined variously a ‘Greater Britain’ spanning large parts of the world, pan-regional imperial structures which united the Anglosphere, and even a world state, all of which were to be buttressed by a ‘color line’ in which race served as the crucial point of demarcation (Bell 2007). A great deal of both IR’s intellectual history, and the historical developments that define many of its current concerns, are rooted in 19th century concerns about the superiority – or otherwise – of white races and Western civilization. Finally, and as we discuss further below, the First World War was not just a beginning, but also an end – the culmination of a series of dynamics which emerged over the preceding century.

Mainstream IR thus prefers to base the discipline on the questionable ‘turning points’ of 1648 and 1919, while marginalizing the more important developments that accumulated between them, especially during the 19th century. This indifference is manifest in the range of textbooks used to introduce IR to students. We examined 89 books commonly listed as key readings for ‘Introduction to IR’ courses. These included both volumes written as textbooks and monographs often employed as introductory readings, such as

Waltz’s Theory of International Politics. The books divided into three groups: IR texts (48), world history texts used for IR (21), and texts aimed more at International Political Economy (IPE) and Globalization studies (20). Of the 48 IR texts, only five contained significant coverage of the 19th century, and those were mostly restricted to post-1815 great power politics (Holsti 1992; Olson and Groom 1992; Knutsen 1997; Ikenberry 2001; Mearsheimer 2001). Seven other texts had brief discussions of the 19th century along similar lines. The majority of IR texts either contained almost no history or restricted their canvass to the 20th century. The appearance of 19th century thinkers was common in books focusing on international political theory, but their ideas were largely discussed in abstracto rather than related to the broader context of the 19th century and its impact on IR. The 19th century fared somewhat better amongst world history texts, although seven of these discussed only the 20th century, and of those, five only surveyed the world since 1945. Of the remaining fourteen volumes, ten either embedded discussion of the 19th century within a longer-term perspective or provided the century with some, albeit limited, attention. Four books gave the 19th century a degree of prominence, especially technological changes which affected military power, but again concentrated mainly on great power politics (Clark 1989; Thomson 1990; Keylor 2001; Kissinger 2003). IPE/Globalization texts fared little better. Three books had no substantive historical coverage, while eight covered only post-1945 or 20th century history. Of the nine books that did mention the 19th century, only two gave it extensive attention (Frieden and Lake, 2000: 73-108, focusing on the rise of free trade; and O’Brien and Williams, 2007: 76-103, looking at how the industrial revolution reworked the distribution of power). Other IPE/Globalization texts tended to treat the 19th century as a prologue to more important 20th century developments.

It is quite possible, therefore, to be inducted into the discipline of IR without encountering any serious discussion of the 19th century. Although mention is often made of the Concert of Europe and changes to the 19th century balance of power, what mainstream IR misses are issues beyond the distribution of power – in other words the transformation of the mode of power initiated by industrialization, the emergence of rational states, and novel ideologies associated with historical progress.

The second way that IR approaches the 19th century is as a site of data accumulation. The Correlates of War project, for example, begins its coding of modern wars in 1816 (e.g. Singer and Small 1972). Some Power Transition Theory also appropriates data from the 19th century in its models (e.g. Organski and Kugler 1980; Tammen ed. 2001). In both cases, there is little rationale for why these dates are chosen beyond the availability of data. Little attention is paid to why data became available during this period (because of the increasing capacity of the rational state to collect and store information). Nor does the transformation of warfare during the 19th century play a prominent role in these accounts. A number of debates between advocates and critics of democratic peace theory (DPT) are also played out over 19th century events such as the War of 1812, the US Civil War, and the 1898 Fashoda crisis (see, for example, Brown ed. 1996). In comparable vein, high profile debates over the efficacy of realist understandings of the balance of power have been conducted over the 19th century Concert of Europe (e.g. Schroeder 1994; Elman and Elman 1995) and, less prominently, over developments in the United States during the 19th century (e.g. Elman 2004; Little 2007). What unites both DPT and realist debates over the 19th century is a failure to read the period as anything other than a neutral site for the testing of theoretical claims. Not only do such enterprises erase the context within which events take place, they also see the 19th century as ‘just another’ period, when it is anything but this. Indeed, the starting point for many of these approaches, the 1815 Congress of Vienna (also found in some liberal accounts of modern international order, e.g. Ikenberry 2001), omits the most significant features of the Napoleonic wars: the legal and administrative centralization ushered in by the Napoleonic code, the French use of mass conscription, the escalating costs of warfare, and the widespread employment of ‘scientific’ techniques such as cartography and statistics (Mann 1993: 214-5, 435; Burbank and Cooper 2010: 229-35). By failing to embed 19th century events within the configuration of global modernity, these accounts tell us little about the transformative character of 19th century international order. Nor do they give sufficient weight to the formative quality of 19th century developments for international relations in the 20th century.

The third way that IR approaches the 19th century is as a partial fragment of a wider research program. For example, both hegemonic stability theorists and neo-Gramscians use the 19th century as a means by which to illustrate their theoretical premises. Robert Cox (1987: 111-50) sees British hegemony during the 19th century as crucial to the formation of liberal world order. The breakdown of this order after 1870, Cox argues, generated a period of inter-imperialist rivalry and fragmentation that was only settled by the ascendance of the US to global hegemony after World War II. Hegemonic stability theorists follow a similar line, although stressing a different causal determinant – a preponderance of material resources (particularly military power) rather than social relations of production.

Robert Gilpin (1981: 130, 144, 185) pays considerable attention to how 19th century British hegemony was premised on the fusion of military capabilities, domination of the world market, and nationalism, highlighting the undercutting of this hegemony late in the century through processes of diffusion and ‘the advantages of backwardness’ possessed by ‘late developers’.

Beyond these two approaches, a number of critical IR theories have usefully examined parts of the 19th century global transformation. Post-structural theorists have stressed the ways in which power-knowledge complexes served to harden inside-outside relations during the 19th century. Jens Bartleson (1995: 241), for example, sees modernity, which he examines through the discourse of late 18th century and early 19th century European thinkers, as a ‘profound reorganization’ of sovereignty, marking the establishment of modern notions of ‘inside’ and ‘outside’. In similar vein, post-colonial theorists have demonstrated how 19th century rhetorical tropes, most notable amongst them narratives of ‘modernization’ and ‘backwardness’, were used to establish practices of dispossession, de-industrialization, and colonialism. This scholarship has also stressed the formative role played by resistance movements, ranging from slave uprisings to indigenous revolts, in subverting Western power and forging counter-hegemonic solidarities (Shilliam 2011). Finally, some feminist scholarship has examined the ways in which 19th century understandings of the status of women were entwined with novel distinctions of public and private in order to construct gendered divisions within Western orders and legitimate discriminatory policies towards ‘primitive’ peoples (e.g. Towns 2009).

Scattered discussion of the 19th century can also be found in a range of diverse IR texts. Daniel Deudney (2007: ch. 6) highlights the importance of the industrial revolution to the violence-interdependence of the modern world and regards the 19th century ‘Philadelphia System’ constructed in the United States as germane to the development of republican international order. Janice Thomson (1994: 12-13, 19, 145-6) sees the disarming of non-state actors such as urban militias, private armies, agents, corsairs, and mercenaries in the 19th century as fundamental to the caging of organized violence within modern states. A number of constructivists also trace contemporary concerns to the 19th century: Martha Finnemore (2003: 58-66; 68-73) argues that the origins of humanitarian intervention can be found in 19th century concerns to protect Christians against Ottoman abuses and in the campaign to end the slave trade; Jeffrey Legro (2005: 122-42) highlights the Japanese move from seclusion to openness in the latter part of the century as an illustration of how the shock of external events combine with new ideas to generate shifts in grand strategy; and Rodney Bruce Hall (1999: 6) argues that the emergence of nationalism during the 19th century was a major turning point in the legitimating principles of international society.

There are three main difficulties with these accounts. First, by looking at parts of the puzzle, they miss the whole. Neo-Gramscian approaches stress relations of production, hegemonic stability theorists focus on power preponderance, constructivists on ideational changes, post-structuralists on discursive formations, and post-colonial theorists on the formative role of colonialism in constructing binaries of ‘civilized’ and ‘barbarian’. No account captures sufficiently the combined, configurational character of the global transformation. Second, more often than not, 19th century events and processes are used as secondary illustrations within broader theoretical arguments – as a result, the distinctiveness of the global transformation is lost. For example, it was not Britain, but a particular configuration of social power resources that was hegemonic during the 19th century. For a time, Britain was situated at the leading edge of this configuration, but only as a specific articulation of a wider phenomenon (Mann 1993: 264-5). Finally, with the exception of post-colonialism and some feminist scholarship, these explanations fail to pay sufficient attention to the non-European dimensions of 19th century international order, reproducing a sense of European mastery which omits the dynamics of empire-resistance and notions of civilizational exchange which helped to constitute global modernity.

The tendency to exclude non-European features of global modernity aligns many of these texts with the fourth way that IR approaches the 19th century – within Eurocentric accounts of the expansion of international society. For many members of the English School, for example, the 19th century is seen as a period in which Western international society completed the expansion process begun during the 16th century (Bull 1984: 118). Traditional figures in the School tended to look upon the 19th century with nostalgia, seeing it as a period in which a relatively coherent Western/global international society flourished. They downplayed the role of imperialism in international society and contrasted its 19th century cultural cohesion with the dilution of international society after decolonization (Bull 1977: 38-40, 257-60, 315-17; Bull and Watson 1984: 425-35). More recently, some English School theorists have used 19th century developments to chart the emergence of hegemony as a primary institution of international society (Clark 2011: chs. 2 and 3) and examined the ways in which leading powers such as China and Japan responded to the coercive expansion of European power (Keene 2002; Suzuki 2005, 2009). Both Keene (2002: 7, 97) and Suzuki (2009: 86-7) stress the ways in which international order during the 19th century was sustained by a ‘standard of civilization’ which bifurcated the world into civilized (mainly European) orders and uncivilized (mainly non-European) polities: rule-based tolerance was reserved for the former; coercive imposition for the latter. These authors not only effectively critique traditional English School accounts in which the expansion of international society is seen as endogenous, progressive, and linear, they also chime with scholarship which stresses the centrality of inter-societal connections and colonial encounters to the formation of modern international order (e.g. Anghie 2004; Shilliam 2011). As such, they provide the basis for a more sustained engagement between IR and the 19th century.

In general, therefore, relatively little IR scholarship adequately assesses the impact of the 19th century on either the development of the discipline or the emergence of modern international order. When the 19th century is mentioned, it is often seen as a site of data accumulation, as a case study within a broader theoretical argument, or as a staging post within a narrative of Western exceptionalism. Only a small body of work highlights central aspects of the 19th century global transformation. These accounts join with the handful of IR texts which see modernity as the basic starting point for the discipline (e.g. Rosenberg 1994). Our argument builds on these accounts to show how global modernity transformed the structure of international order during the long 19th century.

.~`~.

The Global Transformation

For many centuries, the high cultures of Asia were held in respect, even awe, in many parts of Europe (Darwin 2007: 117). India and China were dominant in manufacturing and many areas of technology. As such, the West interacted with Asian powers sometimes as political equals and, at other times, as supplicants. European wealth and power rose during the 17th and 18th centuries, but even until around 1800, there were few differences in living standards between European and Asian peasants – the principal points of wealth differentiation were within rather than between societies (Davis 2002: 16). Nor were there major differences in living standards amongst the most advanced parts of world: in the late 18th century, GDP per capita levels in the Yangtze River Delta of China were equivalent to the wealthiest parts of Europe (Bayly 2004: 2). Overall, a range of quality of life indicators, from levels of life expectancy to calorie intakes, indicates a basic equivalence between China and Europe up to the start of the 19th century (Hobson 2004: 76).

A century later, the most advanced areas of Europe held a tenfold advantage in levels of GDP per capita over their Chinese equivalents (Bayly 2004: 2). Whereas in 1700, Asian powers produced 61.7% of the world’s GDP, and Europe and its offshoots only 31.3%; by 1913, Europeans held 68.3% of global GDP and Asia only 24.5% (Maddison 2001: 127, 263). In 1890, Britain alone was responsible for 20% of the world’s industrial output and, by 1900, it produced a quarter of the world’s fuel energy output (Goldstone 2002: 364). In contrast, between 1800 and 1900, China’s share of global industrial production dropped from 33% to 6%, and India’s from 20% to 2% (Christian 2005: 435).

The rapid turnaround during the 19th century represents a major shift in global power. The extent of this volte-face is captured in Table 1, which uses modern notions of ‘developed’ and ‘third world’ to gauge the gap in production and wealth generated by the emergence of industrialization in the long 19th century. As the table shows, from a position of slight difference between industrial and non-industrial states in 1750 in terms of GNP per capita, the former opened up a gap over the latter of nearly 350% by 1913. And from holding less than a third of the GNP of today’s third world countries in 1750, by 1913, ‘developed countries’ held almost double the level of non-industrialized states.

---------------------------------------------------------------

---------------------------------------------------------------

There are a number of explanations for the ‘great divergence’ between East and West (Pomeranz 2000). At the risk of oversimplification, it is possible to highlight three main modes of explanation: accounts that stress economic advantages; those that focus on political processes; and those which emphasize ideational factors. Economic accounts are divided between liberals and Marxists. Liberals underline several features of the rise of Europe: the role of impersonal institutions in guaranteeing free trade and competitive markets; the legal protection offered by liberal states to finance and industry; and the capacity of liberal constitutions to restrict levels of domestic conflict (North et al. 2009: 2-3, 21-2, 121-2, 129-30, 188). Marxists focus on the ways in which, in north-western Europe, capitalist commodification and commercial exchange extracted productive labor as surplus value, realizing this through the wage contract, and returning it as profit (e.g. Anderson 1974: 26, 403). The marketization of previously personalized relations generated a legal separation between the private realm of the market, mediated by the price mechanism, and the public realm of the state, which served as the institutional guarantor of ‘generalized money’. For Marxists, although the contemporary separation of states and markets appears natural, it is, in fact, historically specific to modernity (Rosenberg 1994: 126).

A second literature focuses mainly on political processes, stressing the particular conditions of state formation which allowed European states to negotiate effectively between elites (Spruyt 1994: 31, 180) and to generate superior revenue flows through efficient taxation regimes (Tilly 1975: 73-4). Some of this literature concentrates on shifts in the means of coercion and, in particular, on the connections between the frequency of European inter-state wars, technological and tactical advances, the development of standing armies, and the expansion of permanent bureaucracies (e.g. Kennedy 1989: 26; Tilly 1990: 14-6; Mann 1993: 1; Bobbitt 2002: 69-70, 346; Rosenthal and Wong 2011: 228-9). In this way, it is claimed, 19th century states combined their need for taxation (in order to fight increasingly costly wars) with support for financial institutions which could, in turn, deliver the funds required for investment in navigation, shipbuilding, and armaments (Burbank and Cooper 2010: 176). ‘War and preparation for war’ gave European states a decisive advantage over polities in other parts of the world (Tilly 1990: 31), even if these advantages were both unintentional and unanticipated (Rosenthal and Wong 2011: 230).

A third set of explanations highlights the role of ideational schemas in the breakthrough to modernity, whether this is considered to have occurred via cognitive advances associated with the Enlightenment (e.g. Gellner 1988: 113-6), the ‘disciplinary’ role played by religions, such as Calvinism, which influenced the routines of modern armies, court systems, and welfare regimes (e.g. Gorski 2003), the emergence in Europe of ‘secular religions’ such as nationalism (e.g. Mayall 1990), or the ways in which ‘the native personality’ was ‘recognized’ through unequal legal practices such as protectorates and, later, mandates (e.g. Anghie 2004: 65-97). Some accounts combine elements from a number of these analyses (Bayly 2004), while others see the ‘great divergence’ as, for the most part, accidental (e.g. Morris 2011).

In this section, we make the case that the shift in global power distribution from Asia to Europe took place because of a novel configuration that linked industrialization, the rational state, and ideologies of progress. This configuration so transformed the means by which power was accumulated and expressed that it generated ‘the first ever global hierarchy of physical, economic, and cultural power’ (Darwin: 2007: 298). The contemporary international order is, in many respects, the inheritor of this 19th century global hierarchy.

Where

Before outlining how the global transformation reconfigured core aspects of both domestic societies and international order, it is important to trace where and when it emerged.

By around 1800, it is possible to speak of a major shift from a ‘polycentric world with no dominant centre’ to a core-periphery hierarchical international order in which the leading edge was in north-western Europe, a previously peripheral part of the Eurasian trading system (Pomeranz 2000: 4; Bayly 2004: 2; Hobson 2004: ch. 7; Darwin 2007: 194; Morris 2011: 557). Traditional explanations of this shift have tended to emphasize endogenous European developments. Eric Jones (1981, xiv, 4, 226), for example, highlights the environmental advantages enjoyed by Europeans (such as a temperate climate which was inhospitable to parasites), demographic issues (most notably, later marriage habits than Asian populations, contributing to lower fertility rates and, in turn, lower population densities), European cultural propensity for ‘tinkering and inventing’, and the development of representational government, which acted to curtail arbitrary power. Other accounts stress the superior accountancy practices of Europeans, particularly double entry bookkeeping which, it is argued, allowed for a clear evaluation of profit, thereby enabling joint stock companies to provide credit in depersonalized, rationalized form – the hallmark of commercial capitalism (North et al. 2009: 1-2). A linked explanation revolves around the better access enjoyed by Europeans to credit and bills of exchange that provided predictability to market interactions and incentivized the development of long-term syndicated debt (e.g. Kennedy 1989: 22-4).

However, such explanations fail to capture the inter-societal dimensions of the global shift in power. First, European success was predicated on imperialism and, in particular, on imperial ‘circulatory systems’ (Gilroy 1993: ch. 3). In this way, the demand for sugar in London furnished the plantation system in the Caribbean, which was supplied by African slaves and North American provisions (Blackburn 1997: 4, 510). Similarly, after the East India Company was ceded diwani (the right to administer and raise taxes) in Bengal, they made the cultivation of opium obligatory, subsequently exporting it to China in a trading system propped-up by force of arms. Through colonialism, European powers exchanged raw materials for manufactured goods, and used violence to ensure low production prices (Pomeranz 2000: 54). The gains from these imperial circuits were high. British profits from the Caribbean plantation system, for example, were worth an average of 9-10% per year to the exchequer during the late 18th and early 19th centuries (Blackburn 1997: 510). Extra-European circuits were fundamental to the global extension of the market – Indian nawabs and Caribbean slave-owning sugar producers were as implicated in global modernity as English industrialists and engineers (Burbank and Cooper 2010: 238).

Second, European advances arose from the emulation and fusion of non-European ideas and technologies: the techniques used in the production of Indian wootz steel, for example, were replicated by Benjamin Hunstsman in his Sheffield workshop, while technologies used in the cotton industry drew heavily on earlier Chinese advances (McNeill 1991: xvi; Hobson 2004: 211-3). These ideas and technologies were carried, in part, via migration: 50 million Europeans emigrated between 1800 and 1914, most of them to the United States, helping to increase the population of the US from 5 million in 1800 to 160 million in 1914 (Rosenberg 1994: 163-4, 168). A ‘settler revolution’, particularly pronounced within the Anglophone world, integrated metropolitan and frontier zones, establishing powerful new transnational linkages (Belich 2011). Up to 37 million laborers left India, China, Malaya and Java during the 19th century (Davis 2002: 208), and an estimated 30 million Indians served as indentured labor in British possessions between 1834 and 1914 (Darwin 2009: 5). The result was an increasingly hybrid feel to communities around the world: hundreds of thousands of Chinese settled on the West coast of North America and in Southeast Asia, as did Indians in East and South Africa, the Pacific islands, and the Caribbean. The 19th century shift in global power, therefore, was fuelled by an intensification in the flows of people, ideas, resources, and technologies – inter-societal processes were a critical part of the European breakthrough (Christian 2005: 364).

When

The global transformation was not a ‘big bang’. In fact, the emergence of industrialization, the rational state, and ideologies of progress was uneven and messy. Aspects of industrialization, for example, were formed in small-scale ‘industrious revolutions’ in which households became centers for the consumption of global products ranging from Javanese spices to Chinese tea (de Vries 2008). Even central nodal points of the global transformation, such as London and Lancashire, contained acute pockets of deprivation. Some British regions, most notably East Anglia and the West Country, experienced declines rather than growth during the 19th century, as did many parts of Europe, including Flanders, Southern Italy, and Western France (Wolf 1997: 297). Even within metropolitan zones, therefore, experience of the global transformation was uneven.

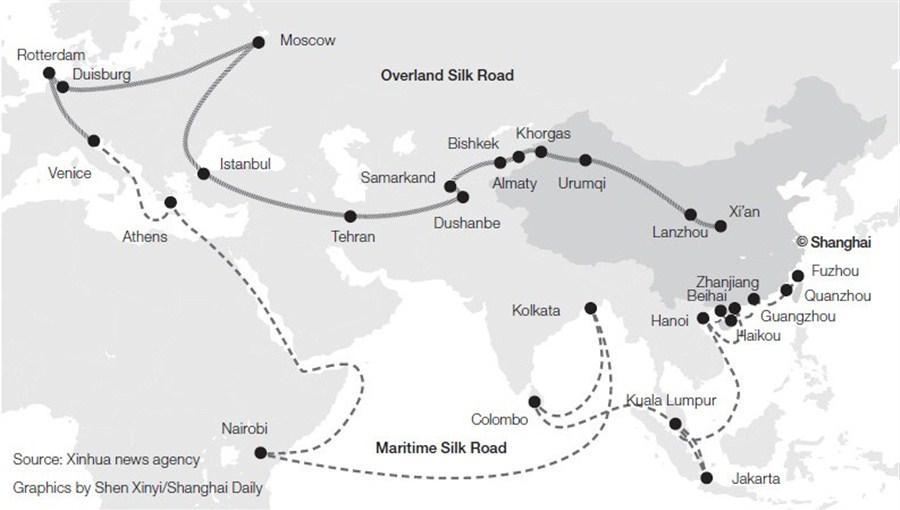

Such issues have fostered considerable debate over both the extent and timing of the global transformation and, in particular, the significance of the shift to industrialization. Some scholarship has pushed the basic transformation of European societies to a later period, usually the first part of the 20th century (e.g. Mayer 2010); others have traced ‘world capitalism’ back to the late 15th century (e.g. Wallerstein 1983: 19) or even earlier (e.g. Mann 1986: 374). It is certainly the case that trade routes connected entrepôts such as Malacca, Samarkand, Hangzhou, Genoa, and the Malabar Coast well before the 19th century. Long-distance commodity chains operating for many centuries leading up to the global transformation established trading networks in silks, cotton, tea, linen, and spices. The use of money and the search for profits during the 19th century did not appear from nowhere.

However, even if commercial capitalist logics – ‘relentless accumulation’ and commodification (Wallerstein 1983: 14-6) – shared affinities with industrial capitalism, the system of the 15th-18th centuries operated on a markedly different scale than its 19th century successor. Most notably, the mutual intensification of both interactive and differential development that characterized the 19th century was distinctive from previous capitalist systems. The marketization of social relations on a vast scale fuelled the growth of a system of densely connected networks, governed through the price mechanism and structured via hierarchical core-periphery relations. In this way, two hundred Dutch officials and a small number of Indonesian intermediaries could run a cultivation system that incorporated two million agricultural workers (Burbank and Cooper 2010: 301). European states established dependencies around the world (such as Indochina for the French), which forcibly restructured local economies, turning them into specialist export-intensive vehicles for the metropole. To take one example, Indian textiles were either banned from Britain or levied with high tariffs, while British manufacturing products were forcibly imported in India without duty (Wolf 1997: 251). Between 1814 and 1828, British cloth exports to India rose from 800,000 yards to over 40 million yards, while during the same period, Indian cloth exports to Britain halved (Goody 1996: 131). This intensified system of market interdependence was buttressed by powerful rhetorical tropes: Europeans reinvented African clans as ancient tribes, and hardened Indian caste status into a formal administrative system in order to demonstrate the ‘backwardness’ of ‘uncivilized’ peoples (Darwin 2007: 15). No system in world history so united the planet, while simultaneously pulling it apart.

The first stage in this process was the commercialization of agriculture. Legislation such as the 1801 Great Enclosures Act in Britain, the codification of practices that had built up over preceding centuries, privatized the commons and turned land into a productive resource. Mechanization and the adoption of cash cropping restructured the landlord-peasant relationship as a commercial relation between landowners, tenant farmers, and landless laborers. From this point on, labor power was bought and sold as a commodity (Wolf 1997: 78). Those forced off the land usually moved to cities, which expanded quickly as a result: between 1800 and 1900, London grew from just over 1 million to 6.5 million inhabitants, the population of Berlin rose by 1000%, and that of New York by 500% (Bayly 2004: 189). The commercialization of agriculture was a process repeated, in varying forms, around the world. As profits could only be achieved through higher productivity, lower wages, or the establishment of new markets, expansion of the system was constant, leading to the development of both new areas of production (such as southeastern Russia and central parts of the United States) and new products (such as potatoes). Development was often rapid: in 1900, Malaya had around 5,000 acres of rubber production; by 1913, it contained 1.25 million acres (Wolf 1997: 325). In short: ‘free trade was a crash program in social transformation’ (Rosenberg 1994: 168).

The worldwide commercialization of agriculture was a stepping-stone in the development of industrial capitalism, providing a logic by which sectors from textiles to armaments took shape. Industrialization emerged in two main waves. The first (mainly British) wave centered on cotton, coal, and iron. The crucial advance was the capture of inanimate sources of energy, particularly the advent of steam power (McNeill 1991: 729). Britain’s lead in this field presented a major advantage – by 1850, 18 million Britons used as much fuel energy as 300 million inhabitants of Qing China (Goldstone 2002: 364). Also crucial was the application of engineering to blockages in production, such as the development of machinery to pump water efficiently out of mineshafts (Morris 2011: 503). Engineering and technology combined to generate substantial leaps in productivity: whereas a British spinner at the end of the 18th century took 300 hours to produce 100 pounds of cotton, by 1830 it took only 135 hours (Christian 2005: 346).

Towards the end of the 19th century, a second (mainly German and American) wave of industrialization took place, centering on advances in chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and electronics. Once again, new sources of energy were critical, such as the distillation of coal into tar for use in products ranging from explosive to dyes, and the application of chemicals to the manufacture of steel and other alloys. Perhaps most notably, advances in light metals and electrics, allied to the use of oil for fuel, provided an impetus to the development of cars, planes, and ships (Woodruff 1966: 181-2; McNeill 1991: 737). The closeness of industry and the state in many countries, particularly Germany, stimulated the emergence of cartels, which took over the whole productive process, from the supply of raw materials, to manufacturing, wholesale, and retailing. The enmeshing of ‘big capital’ and the ‘big state’, heightened by protectionism, intensified geopolitical competition in the period leading up to World War One. The resulting conflict was the culmination of pressures that had built for much of the latter part of the 19th century.

Beyond the debates about the ‘when’ of industrialization lie similar questions about the emergence of the rational state. Not only did empires remain key sites of political authority during the long 19th century, but some scholarship sees rational states as emerging before this period, pointing to the impact on state administrative capacities of the ‘military revolution’ of the 16th and 17th centuries (Downing 1992: ch. 3; Mann 1986: 445-6; Mann 1993: 1), and the 18th century development of states as calculating ‘power containers’ responsible for the certification of fiduciary money (Giddens 1985: 13, 126-8, 153). As with debates about the emergence of industrialization, it is clear that a range of antecedent processes enabled the rise of the rational state during the 19th century. But it was only during the 19th century that states attempted to assume monopolistic control over the use of legitimate force within a particular territory – authority over domestic conflicts shifted from being ‘dispersed, overlapping, and democratized’ to being ‘centralized, monopolized, and hierarchical’ (Thomson 1994: 3). In the 18th century, institutions such as the Dutch East India Company had a constitutional warrant to ‘make war, conclude treaties, acquire territory, and build fortresses’ (Thomson 1994: 10-11). However, particularly after the French Revolution, armies and navies became more distinctly national, coming under the direct fiscal control of the state. International agreements restricted the use of mercenaries and sought to eliminate privateering. At the same time, states took over competences previously the task of local intermediaries, including policing, taxation, and censuses (Tilly 1990: 23-9). Although nation-states co-existed with empires, dependencies, and colonies – and some nation-states, such as Britain, were both states and empires simultaneously – there was a notable ‘caging’ of competences within states, itself enabled by the rise of nationalism and popular sovereignty. These ideologies both legitimized state borders and presented the outside world as an alien space. Imperial expansion into these alien spaces went hand-in-hand with the emergence of the sovereign nation-state. Both were seen as the ‘progressive’ hallmarks of ‘civilized’ states (Anghie 2004: 310-20).

How

The configuration of industrialization, the rational state, and ideologies of progress was a powerful ‘social invention’ (Mann 1986: 525), capable of delivering progress both domestically through linking industrialization with state capacity, infrastructural change, and scientific research, and internationally through coercive interventions in trade, production, and financial regimes, and through the acquisition of new territories.

During the mid-to-late 19th century, the industrial powers established a global economy in which the trade and finance of the core penetrated deeply into the periphery. During the century as a whole, global trade increased twenty-five times over (Darwin 2007: 501). As the first, and for a time only, industrial power, it was British industrial and financial muscle that led the way. British production of pig iron quadrupled between 1796 and 1830, and quadrupled again between 1830 and 1860 (Darwin 2009: 19). British foreign direct investment, led by London’s role as the creditor of last resort, rose from $500m in 1825 to $12.1b in 1900 and $19.5b by 1915 (Woodruff 1966: 150; Sassen 2006: 135-6). The industrial economy was constructed on the back of improvements engendered by railways and steamships, and by the extension of colonization in Africa and Asia – between 1815 and 1865, Britain conquered new territories at an average rate of 100,000 square miles per year (Kennedy 1989: 199). The opening-up of new areas of production greatly increased agricultural exports, intensifying competition and pushing down agricultural incomes (Davis 2002: 63). The agrarian fear of famine remained. But this fear was joined by modern concerns of overproduction, price collapse, and financial crisis (Hobsbawm 1975: 209). The 19th century’s great depression between 1873 and 1896 was the precursor to 20th century industrial and trade cycles (Hobsbawm 1975: 85-7).

These changes eroded local and regional economic systems, and imposed global price and production structures (Darwin, 2007: 180-85, 237-45). The consequences of these policies were often extreme. Famines and associated epidemics in the 1870s and 1890s killed millions of people around the world – at least 15 million in India alone (Davis 2002: 6-7). Famines were the direct consequence of the expansion of the market and the forceful commercialization of agriculture. In India, for example, land and water were privatized under British direction so that they could be used as a taxable resource. At the same time, communal stores were forcibly removed from villages so that basic foodstuffs could be sold commercially. Dispossession meant that, when droughts hit in 1877, many Indians could not afford either food or water. The British reacted by reducing rations to male coolies to just over 1,600 calories per day – less than the amount later provided in Nazi experiments to determine minimum levels of human subsistence (Davis 2002: 38-9). Similar processes took place in China (whose ‘ever-normal’ granaries were closed to pay for trade deficits caused by military defeat in the Opium Wars and the unequal treaties signed with European powers) and many parts of Africa (Davis 2002: 6). The extension of the market generated a core-periphery order in which the ebbs and flows of metropolitan markets, commodity speculations, and price fluctuations controlled the survival chances of millions of people around the world. Accelerating market integration served to amplify differences between nodes of the world economy (Bayly 2004: 2). The industrial core adapted production and trade in the periphery to its needs, setting up the modern hierarchy of labor between commodity and industrial producers. This division of labor and its accompanying social upheavals was first established in the 19th century; it was to dominate international political economy in the 20th century.

The role of industrialization in generating a core-periphery world market was conjoined with the emergence of the rational state. During the 19th century, states became staffed by permanent bureaucracies selected by merit and formalized through impersonal legal codes. The technocratic-bureaucratic features of rational states grew interdependently with industrialization. Prior to modernity, economic relations were generally political tools by which elites exerted their authority: property and title went hand-in-hand with administrative offices; taxation was often contracted out to private entrepreneurs; and landlord-peasant relations were conducted directly through mechanisms such as corvée (Anderson 1974: 417-22). In modernity, by contrast, the shift to economies mediated by prices, wage-contracts, and commodities generated a condition in which states provided the institutional guarantees for market transactions, and assumed the monitoring and coercive functions required for capitalist expansion.

The emergence of an apparently discrete political sphere furnished the conditions for the emergence of mass politics – what Michael Mann (1993: 597) calls ‘popular modernity’. Millions of Britons joined the Chartist movement and the campaign against the slave trade during the first half of the century, and millions more around Europe joined trade unions, left-wing political parties, friendly societies, syndicalist movements, and other radical groups during the second half of the century. The 1848 revolutions and the experience of the Paris Commune, allied to the capacity of anarchist groups to carry out high-profile assassinations, meant that even absolutist states were forced into reforms. Pressures for absolutism to become more ‘enlightened’ and for parliamentary systems to become more republican fostered demands for political representation (met by successive British Reform Acts), the provision of welfare (as in Bismarck’s ‘social insurance’ scheme), and mass education (which helped to increase rates of literacy and, in turn, fuel the rise of the mass media). Some of this was ‘decoration’ as old regimes sought to maintain their authority (Tombs 2000: 11). But fear of ‘the social problem’ was widely felt. As a consequence, state bureaucracies encroached on areas previously the preserve of guilds, municipal corporations, provincial estates, charities, religious orders, and other such bodies. During the second half of the century, state personnel grew from 67,000 to 535,000 in Britain and from 55,000 to over a million in Prussia/Germany; during the same period, state-military personnel tripled in Britain and quadrupled in Prussia/Germany (Mann 1986: 804-10).

Key to the emergence of the rational state was improvements in infrastructure. Widespread railway building began in Britain during the 1820s, before spreading to France and Germany during the 1830s. By 1840 there were 4,500 miles of track worldwide, expanding to 23,500 miles by 1850, and 130,000 miles by 1870; by the end of the century, there was half a million miles of track worldwide, over a third of which was in Europe (Hobsbawm 1962: 61). This expansion had a major effect on both trade and state administration. In 1850, it could take up to three weeks to cross the continental US by a combination of train and stagecoach; the coming of the transcontinental railways in 1869 reduced the journey to five days. Early railways reduced overland transportation costs by between half and three quarters; early 20th century railways reduced these costs between 9 and 14 times in Britain, and between 30 and 70 times in the United States (Woodruff 1966: 225, 254).

Other infrastructural developments also helped to boost state capacity. The impact of the telegraph, for example, was far-reaching. Communication times between Britain and India dropped from a standard of around six months in the 1830s (via sailing ship), to just over one month in the 1850s (via rail and steamship), to the same day in the 1870s (via telegraph). By the late 19th century, telephones began to succeed the telegraph, replacing cumbersome coding and decoding processes with direct voice communication. The ability to broadcast via radio meant that communication became not only instantaneous, but also flexible. After 1901, radio extended communication networks to ships and, by 1907, there was a regular transatlantic radio link. These developments had major impacts on state rationalization. Governments could find out about political and military developments almost as soon as they happened, while concentrated command structures could be extended over long distances. The result was increasing state coordination of both domestic and foreign affairs, fuelled partly by improvements in infrastructural capabilities and partly by the emergence of powerful ideologies such as nationalism. Not only did nationalism shift the locus of sovereignty from ruler to people, it also identified the territory of the state with the people rather than seeing it as determined by hereditary rights or dynastic inheritance. When the absolutist state became the nation-state, territory became sacralised (Mayall 1990: 84). Nationalism facilitated the overcoming of local identities, increasing the social cohesion of the state through the cultivation of national languages, themselves the result of national education systems and the advent, in many places, of national military service.

Rational states were sustained, therefore, by the emergence of industrialization, mass politics, infrastructural developments, and nationalism. They also grew through imperialism: the modern, professional civil service was formed in India before being exported to Britain; techniques of surveillance, such as fingerprinting, were developed in the colonies and subsequently imported by the metropole; while imperial armies played leading roles in wars around the world (Bayly 2004: 256). Imperial wars and armed settlements increased the coercive capacities of states, while requiring that states raise extra revenues, which they often achieved through taxation. This, in turn, fuelled further bureaucratization. The 19th century, therefore, represented a major increase in the capacity of states to fight wars, regulate their societies, and coordinate their activities. Domestically, rational states provided facilitative institutional frameworks for the development of industry, technological innovations, weaponry, and science; abroad, they provided sustenance for imperial policies. Both functions were underpinned by ideologies of progress.

Industrial society was the first to ‘invent progress as an ideal’ (Gellner 1983: 22). Beginning in the 1850s, ‘great international exhibitions’ provided showcases for state progress (Hobsbawm 1975: 49). Industrialization consolidated expectations of progress by normalizing technological change – innovation and research became a permanent feature of both state and private activity. German research labs led the way, pioneering developments in chemicals, pharmaceuticals, optics, and electronics. Private labs followed: General Electric set up a research lab in commercial dynamos in 1900, followed by DuPont’s chemicals lab in 1902. During the same period, academic disciplines and societies emerged for the first time, aiming to systematize branches of knowledge (Gellner 1988: 116). ‘Expert systems’ of licensing and regulation gathered information and codified data (Giddens 1985: 181).

The idea of progress went further than the professionalization of research and the formalization of knowledge. Major 19th century ideologies, from liberalism to socialism, contained an inbuilt drive towards the ‘improvement’ of the human condition. Even the ‘scientific’ versions of racism that became increasingly prominent in the last quarter of the century contained a progressive element, imagining a world in which ‘superior stock’ took command of the modern project. Ideas of progress were bound up with the experience of empire, based on a comparison between core and periphery, which reflected the metropolitan sense of superiority. This is captured well by the notion of the ‘standard of civilization’.

The global transformation altered the relationship between the West and Asian civilizations from being relatively egalitarian politically, and respectful culturally, to being dominant politically and economically, and contemptuous culturally (Darwin 2007: 180-217). The result was a ‘Janus-faced’ international society in which Western powers practiced sovereign equality amongst themselves, while imposing varying degrees of inferior status on others (Anghie 2004: ch. 2; Suzuki 2005: 86-7). Inequality came in many forms: unequal treaties and extraterritorial rights for those polities left nominally independent (like China); partial takeovers, such as protectorates, where most local government was allowed to continue, but finance, defense, and foreign policy were handled by a Western power (as in the case of Sudan); and formal colonization, resulting in elimination as an independent entity (as in India after 1858). By 1914, colonization by Europeans or colonizers of European origin covered 80% of the world’s surface (not including uninhabited Antarctica) (Blanning 2000: 246). It is no surprise, therefore, that those states, like Japan, which sought to emulate European power, underwent both a restructuring of domestic society through industrialization and state rationalization, and a reorientation of foreign policy towards ‘progressive’ imperialism: Japan invaded Taiwan in 1874 (annexing it formally in 1895), fought wars for overseas territory with both China (1894-5) and Russia (1904-5), and annexed Korea in 1910 (Suzuki 2005: 138). Becoming a civilized member of international society meant not just abiding by European legal frameworks, diplomatic rules, and norms; it also meant becoming an imperial power.

Imperialism, therefore, was closely bound up with ideas of progress that were themselves interwoven with industrialization and the emergence of the rational state.

The result was a powerful configuration that transformed both domestic societies and international order. Central to this configuration was European efficiency at killing.

.~`~.

The Organization of Violence

In this section, we illustrate the transformative effect of global modernity on the organization of violence during the 19th century. We focus on two dynamics: the generation of a power gap between core and peripheral states, and the destabilization of great power relations by industrial arms racing. These two dynamics remain central to contemporary international relations.

During the 19th century, particularly as the industrial revolution began to accelerate and spread, the character of military relations changed markedly (Pearton 1982; Giddens 1985: 223-6). Although many important changes to military techniques, organization, and doctrine took place in the centuries preceding the 19th century (Parker 1988; Downing 1992), modernity served as a new foundation for achieving great power standing. Manpower still mattered, so that a small country such as Belgium could not become a great power no matter how industrialized it was (although it could still become an imperial power). But the level of wealth necessary to support great power standing could now come only from an industrial economy. Equally important was the way in which industrial economies supported a permanent rate of technological innovation. Firepower, range, accuracy, and mobility of existing weapons improved, and new types of weapons offering new military options began to appear. For example, between the middle and end of the 19th century, the invention of machine guns lifted the potential rate of fire of infantrymen from around three rounds per minute for a well-trained musketeer to several hundred rounds per minute. The revolution in the means of production helped to generate a revolution in the means of destruction.

This development is best illustrated by examining changes in naval power. Ever since they first intruded into the Indian Ocean trading system in the late 15th century, Europeans held an advantage in sea power. Their ships were better gun platforms than those of the Indian Ocean civilizations, one of the few technological advantages that favored the Europeans before the 19th century. Europeans were able to establish ‘maritime highways’ through coastal trading cities such as Cape Town, Singapore, and Aden, and treaty ports like Shanghai (Darwin 2007: 16). Nineteenth century technological developments massively accelerated these advantages.

FIG 1. The technological development of naval weapons, 1850-1906

Up to 1850 (HMS Victory)

1860 (HMS Warrior)

1871 (HMS Devastation)

1906 (HMS Dreadnought)

As illustrated in Figure 1, from the mid-19th century, technologies of wood and sail rapidly gave way to industrial technologies of steel and steam. HMS Victory represents the culmination of agrarian technology: wood and sail ships of the line, which had followed a broadly similar design from the 17th century until 1850. HMS Warrior characterizes the first stage of the breakthrough to iron construction and steam power. HMS Devastation marks the completion of the turn to iron and steam construction. HMS Dreadnought demonstrates the breakthrough to the fully modern battleship.

The transformation from wood and sail to steel and steam took just fifty years. Across this half-century there was: a 33-fold increase in weapons range from 600 yards (Victory) to 20,000 yards (Dreadnought); a 26-fold increase in weight of shot from 32 pounds solid shot to 850 pounds explosive armor-piercing shell; more than a doubling of speed from 8-9 knots (Victory) to 21 knots (Dreadnought); and a shift from all sail (Victory) to steam turbines (Dreadnought), permitting all-weather navigation for the first time. From the 1860s onward, each generation of warship made obsolete those that had preceded it. The metal-hulled Warrior was the most powerful warship of her day, able to sink any other ship afloat. But within a few years it would have been suicidal to take it into a serious engagement against more modern ships.

Rapid innovation on this scale was a general feature of the 19th century, particularly after the 1840s. It underpinned three ongoing problems of military modernity. First, there was both the hope of gaining a rapid technological advantage and the fear of being caught at a strategically decisive disadvantage. Second, in some minds, the constant increase in powers of destruction raised fears of military capabilities outrunning prudent policy-making. Third, there was the worry that great power status could only be maintained by keeping up with new weaponry; any failure to stay at the leading edge could result in the loss of relative military power and the danger of being defeated by rivals equipped with more modern weapons. The shift from wood and sail to iron and steam generated arguably the first modern industrial arms race between Britain and France during the 1860s and 1870s, fuelled by British fears that possession of a handful of the most modern warships could give France the ability to defeat the larger, but less modern, British navy, and so gain strategic control of the English Channel. This new factor added a powerful element to the security dilemma that is characteristic of modernity, but which was largely absent from great power relations in the agrarian era (Pearton 1982). The destabilization of great power relations by relentless, qualitative improvements in military equipment has subsequently become a central concern for IR; it is almost the defining issue of Strategic Studies.

The links between industrial production, technological innovation, and equipment, along with shifts in military organization and doctrine, were the foundations of the core-periphery order that developed during the 19th century. In the front line, the main military technologies were quick firing breech-loading rifles, machine guns, modern shell-firing artillery, and steam powered iron warships. These were backed-up both by the logistical capabilities of railways and steamships, and by the rapid communications enabled by the telegraph (Giddens 1985: 224-5). Two examples illustrate the extent of the resulting power gap. During the first opium war against China (1839-42), a minor British warship (the steam sloop Nemesis) had no difficulty using her superior firepower and maneuverability to destroy a fleet of Chinese war junks. Similarly, at the battle of Omdurman in 1898, a force of some 8,000 British troops equipped with modern artillery and machine guns, and backed by 17,000 colonial troops, took on a rebel army of some 50,000 followers of the Mahdi. In a day’s fighting, the British lost 47 men, the rebels around 10,000. Military superiority, allied to broader advances in political economy, organization, and strategy, allowed European states to intimidate, coerce, defeat, and if they wished, occupy, territories in the periphery.

Western powers were concerned to maintain their advantage by denying, or restricting, access to advanced weapons. This posed an enduring problem, because as well as wanting to restrict the access of non-European colonial peoples to modern arms, most colonial powers used colonial troops to administer and extend their empires. Indian police officers, bureaucrats, and orderlies served the British state in China, Africa, and the Middle East, while Indian troops fought in British wars in China, Ethiopia, Malaya, Malta, Egypt, Sudan, Burma, East Africa, Somaliland, and Tibet (Darwin 2009: 183). Such ‘foreign forces’ continued to play a leading role in colonial armies during the 20th century (Barkawi 2011: 39-44). At the same time, resistance to empire in many parts of the world including Latin America, the North West Frontier, Indochina, and the African interior, meant that these regions were never fully pacified. Resistance movements, making extensive use of terrain, locally embedded social networks, and guerrilla tactics, became the seeds for the unraveling of Western empires in the 20th century.

The focus by IR scholarship on the ‘long peace’ enjoyed by European powers during the 19th century therefore sits at odds with the experience of those at the wrong end of the global transformation – between 1803 and 1901, Britain was involved in fifty major colonial wars (Giddens 1985: 223). However, the sense of bifurcation between war abroad and peace at home, did have significance for the development of international order, reinforcing a sense of European cultural and racial superiority which facilitated its coercive expansions around the world (Anghie 2004: 310-20; Darwin 2007: 180-5, 222-9). Yet while the industrialization of military power gave the whip hand to the core over the periphery, it also introduced qualitative arms racing, arms control, and questions about the rationality of war into the heart of great power relations. The transformation in modes of organized violence during the 19th century thus provides a common foundation to two narratives in IR that are normally treated as separate: the volatility of the balance of power amongst the great powers, and the relative stability of the imbalance of power between the core and the periphery. The 19th century also features the rise of Japan as making the first linkage between these two stories as Japan moved from periphery to core. As Britain’s lead in industrialization began to recede, so its dominance was reduced by newer powers, such as Germany and Japan, better adapted to the second generation of industrial technologies and just as capable of aligning this with state rationalization and notions of progress. The relative decline of Russia, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire was a consequence of their lack of success at adapting to the global transformation. For the larger European powers, overseas empires became an alternative measure of their standing. Down this path lay latecomer claims to ‘a place in the sun’ and the rivalries that helped pave the way to the First World War, the Second World War, and the Cold War.

.~`~.

Conclusion

We have argued that the configuration that marked the transformation of domestic societies and international order during the 19th century serves as an important guide to understanding both the emergence of modern international society and core features of contemporary international relations. If this claim stands up, then IR needs to rethink many of its principal areas of interest and reconsider how it defines much of its contemporary agenda.

One way of illustrating this point is to outline an alternative set of IR benchmarks to those highlighted in the introduction, all of which are located in the ‘long 19th century’:

• 1789: The French revolution unleashes republicanism and popular sovereignty against dynasticism and aristocratic rule, while making use of novel organizing vehicles such as the levée en masse.

• 1840: This date roughly signifies when the cloth trade between India and Britain was reversed, illustrating the turnaround of trade relations between Europe and Asia, and the establishment of an unequal relationship between an industrial core and a commodity supplying periphery.

• 1842: The First Opium War sees the British defeat the greatest classical Asian power, helping to establish a substantial inequality in military power between core and periphery.

• 1857: The 1857 Indian Revolt (often referred to as the Indian Mutiny) causes Britain to take formal control of the sub-continent, while serving as the forerunner to later anti-colonial movements.

• 1859: The launching of the French ironclad warship La Gloire opens the era of industrial arms racing in which permanent technological improvement becomes a central factor in great power military relations.

• 1862: The British Companies Act marks a shift to limited liability firms, opening the way to the formation of transnational corporations as significant actors in international society.

• 1865: The International Telecommunications Union becomes the first standing intergovernmental organization, symbolizing the emergence of permanent institutions of global governance.

• 1866: The opening of the first transatlantic telegraph cable begins the wiring together of the planet with instantaneous communication.

• 1870: The unification of Germany serves as an indication of the standing of nationalism as an institution of international society, as well as highlighting a central change in the distribution of power.

• 1884: The Prime Meridian Conference establishes world standard time, serving to facilitate the integration of trade, diplomacy, and communication.

• 1905: Japan defeats Russia and becomes the first non-Western (and non-white) imperial great power.

Such benchmarks help to reorient IR around a series of debates which are germane to contemporary international relations: a) the emergence and institutionalization of a core-periphery international order which was first established during the global transformation; b) the ways in which global modernity has served to intensify inter-societal interactions, but also amplify differences between societies; c) the closeness of the relationship between war, industrialization, rational state-building, and standards of civilization; d) the central role played by ideologies of progress in legitimating policies ranging from scientific advances to coercive interventions; and e) the centrality of dynamics of empire and resistance to the formation of contemporary international order. In short, a rearticulation of IR around the dynamics of the global transformation means examination of how industrialization, the rational state, and ideologies of progress generated the configuration within which much of contemporary international relations works, yet which most IR theories do not accommodate.