.~`~.

I

Francis Fukuyama

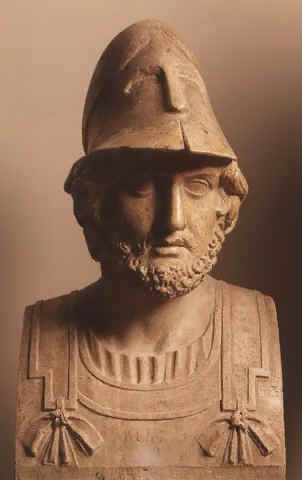

Francis Fukuyama | China is important in the world’s history in terms of the development of its state. In the West, the typical accounts of development of institutions tend to be very Euro-centric, taking the experience of European countries as the norm. They fail to recognize the fact that China was the first country to create a modern state 1,700 or 1,800 years earlier than in Europe.

There are three categories of political institutions in the world. The first institution is the state. The state is a hierarchical organization that concentrates and uses power to enforce rules in certain areas. The state is about the ability to coerce people. What is a modern state? I use the definition of Max Weber. The modern state is not based on friends and families. People should not be hired based on what relationship they have with the ruler. Rather they should be treated impersonally as citizens with a certain impersonal distance from the ruler as opposed to ancient states which were ruled on the basis of families or the kinship of rulers.

The second category of political institution is the rule of law. The rule of law is not just about having laws. Every country has its own laws, but laws must represent a moral consensus in the community that is higher than the will of whoever runs the state. So in other words, if the emperor, the president, the king or the prime minister makes up laws according to his own will, that is not the rule of law. The rule of law means even the highest authority in the country should abide by the laws.

The final set of political institutions has to do with political accountability whereby the government feels a responsibility towards its people as opposed to ruling purely in its own interests. There are many countries in the world where rulers regard countries as a means to enrich themselves and their families. That is not an accountable government. In the US and other Western countries, we associate accountability with democracy. Political accountability is broader than simply democratic elections.

The earliest form of accountability that emerged in Europe was in England in the 17th century. That was the accountability of the monarch to a parliament that only represented about 1 percent of the English population. This would not be qualified as democracy in any modern sense. But in China, I believe everyone knows the fact that you have had moral accountability, meaning that the government is not totally accountable through election, but feels a sense of responsibility to the public based on the education and training of the emperors/rulers. This is, I believe, the dominant understanding of accountability in China—moral accountability.

So states concentrate power, then the rule of law and political accountability set the limits. No matter how powerful a government is, it should be constrained by the rule of law and be held accountable to its people.

As I said, the first state in the world was created by China. The motive was actually the same as it was in Europe—the pressure of military competition. During the Spring-Autumn Period and Warring States Period in ancient Chinese history, you have multiple Chinese political entities fighting over 700 years. And that military competition forced the formation of modern political institutions. It required taxation, required recruiting officials to collect taxes and required promotion on merit. If you hired your family relatives and not the best military officers, you were not going to win the war.

Already at the time of the Qin Dynasty, the first dynasty that unified China, China already developed a state that looked remarkably modern. The civil servants examination was invented in due course. You had bureaucracy that was organized on rational lines and military forces in a large territory that were organized by unified rules. This creation of a modern state, created about 2,300 years ago in 221BC was a great historical achievement.

What China didn’t develop is the other two political institutions: rule of law and formal institutions of political accountability. The reason that China did not have the rule of law is that China did not have a dominant religion. I believe rule of law in most societies originated out of religion because religion usually serves as the source of moral rules that in many societies are administered by a separate legal hierarchy: judges, juries and priests. This was true in ancient Jewish Israel, in the Christian West, in Islam and in Hindu India. In all these societies you have legal constraints over the power of executives. However China did not have such independent religious support. That is not part of the Chinese tradition. So formal democratic accountability did not occur.

The West has developed quite differently. In the feudal time of Europe, it started with the rule of law. The Catholic Church devised the Code in the 11th century even before there was a modern European state. The European monarchs, like their counterparts in China, began to create centralized, bureaucratic powerful states in the 16th and 17th century. But they had to do so against the background of the prior existing legal constraints which limited their ability to concentrate power.

The origin of democracy in the West was the product of historical accidents. All feudal Medieval European countries had institutions called parliaments, diets or the sovereign court. These were the organizations that the King had to go to if he wanted to increase taxes. In England, the parliament was effectively strong and actually fought a civil war with the King. King James II was overthrown in 1688 and replaced with a monarch that was chosen by the Parliament. So the idea of accountability to an elected parliament really began with the Glorious Revolution of 1688. In many respects, the emergence of democracy in Europe was the result of this English development. That was, to some extent, remarkable. The rule of law and accountability turned out to be very powerful because they were the basis for the protection of property rights in England, the development of a powerful modern economy, the rise of capitalism and the industrial revolution.

These are the bases of the governing institutions we see today in the West. Obviously there are many differences between China and the West. Today China is ruled by the Communist Party whose doctrine is Marxism, not Confucian ideology. But in many other respects, the governance structure in China is very similar to the pattern established in the Qin Dynasty. High quality centralized bureaucratic government is built on impersonal recruitment and formal rules. That is the historical background.

Now let me talk about the China Model. How is it constituted? What are its strengths and weaknesses? What kind of system is the Chinese system? The first characteristic is a centralized, bureaucratic and authoritarian government. It’s legacy comes from earlier Chinese history in which there was high degree of institutionalization within the government and within a very complex bureaucracy ruling over an extremely large society. In today’s form of government, accountability goes upward primarily to the Communist Party instead of going to the Emperor. There is accountability in that system.

If you are an official and the government wants to punish you, they can hold you accountable. But there is no downward accountability to people who are being ruled. This contrasts with procedural accountability through democratic elections. That is modern democratic accountability.

Chinese accountability has been moral rather than procedural. Moral accountability means rulers feel morally accountable to their people. If you look around the world at the successful modernized authoritarian regimes, they are all clustered in East Asian countries such as South Korea, Taiwan under the Kuomintang, Singapore under Lee Kuan Yew, Japan in its early stage when democracy was not existent, and of course, The People’s Republic of China.

In other words, this kind of accountability is more or less confined to Chinese culture. In the Confucian way, there is a tradition of moral accountability. There are many authoritarian governments where rulers believe politics is about stealing wealth from other people and giving it to their families or friends. That is not the Chinese tradition.

The second element of the China Model is economic. Here I don’t think China is so much different from other fast-growing countries in East Asia. Like them, the China Model has been based on export orientation and relatively active government policies that promote industrialization. At the same time, it is a little bit different from policies implemented by Korea and Japan. In the Chinese case, industrial policies are less clearly targeted, for example, on semi-conductors, steel or ship-building. Generally speaking, the Chinese government is more focused on infrastructure facilities, financing, and a currency regime to make its exports more competitive rather than picking any particular winners in the economy. Nevertheless China has not been prone to rely on the market economy in its development.

The fourth element of the China Model is a relatively modest social safety net when compared with other developed countries, particularly those in Continental Europe or Scandinavia. China has tried to create a high level of employment, but started at a low level. More should have been done to help the poor and narrow the wealth gap despite the fact that China nominally remains a Marxist society. So one of the results is that Gini coefficient, which is used by economists to measure inequality, has been going up rapidly over the past few generations. Obviously the Chinese government recognizes this is a problem. The gap of living standards between cities like Shanghai and the interior areas is wide. Scandinavian countries such as Denmark and Norway are largely welfare states and support low-income families while China up to this stage has done little.

Now let’s compare these two sets of institutions and look at their own advantages and weaknesses respectively. One the one hand, we have the China Model. On the other hand there is the liberal democratic model which is represented by those democratic states including the UK, the US, France, Italy and of course some developing countries such as India.

The China Model has some key advantages, one of which is its decision-making processes. In this aspect, the difference between China and India is quite obvious. China is strong in building infrastructure facilities: large airports, high-speed railways, bridges and dams because the centralized government structure makes it faster to implement these projects. India, a country in the tropical zone, has abundant precipitation. However its hydropower infrastructure is nowhere close to China. Why? Because India is a law-based democratic government.

When China was building the Three Gorges Dam, there was a lot of opposition and criticism. But the government built the dam by its own will. By contrast, years ago, Tata Auto wanted to build a vehicle company in west Bangalore. There were strikes, protests and even lawsuits by trade unions and peasant organizations. The idea finally yielded to strong political opposition.

So in certain economic decision-making, the authoritarian Chinese system has its advantages. In the case of the US, we have a law-based government and formal democratic accountability. The US is not as bad as India in terms of decision-making, but we have our own problems in the political system, for example, the long-term fiscal deficits. Every expert knows that this is not sustainable and has been made even worse by the recent financial crisis, but our political system is largely paralyzed in doing anything about it by the confrontation between the Democrats and the Republicans.

Our interest groups are very powerful and capable of blocking some decisions. Although these decisions may be rational in the long term perspective, they are not taken in the end simply because of the opposition from some interest groups. It is a tough issue to be addressed in the US. Whether we can change this state of affairs over the next few years is important in judging whether the democratic system of the US can be successful in the long run.

China does have a lot of other advantages not particularly rooted in the Chinese history and culture. Compared with the last generation, the Chinese today are relatively free from ideology. The government has tried many innovations. If they work, it goes with them. If not, it drops them. Meanwhile the US government is actually rigid in making economic policies. Although the US is known for being pragmatic and willing to try new things, I actually don’t take that view.

So China does have many advantages. But the question is sustainability. After the financial crisis, China has done very well while the US doesn’t look good and is struggling with fiscal deficits. But which system is more sustainable in the next two to three decades? My preference is still for the American system rather than the Chinese system.

There are several issues that deserve our attention in the Chinese political system. Firstly, the lack of downward political accountability. If you look at the dynastic history in China you often see that a highly centralized bureaucratic system with insufficient information and knowledge of the society results in ineffective governance. What bureaucracy brings is corruption and bad governance. To some extent, this problem can still be observed in China today.

Of course there are many opportunities to collect information. For example we have the Internet and many other modern communication technologies. However it remains an issue whether the government is able to respond to popular requirements and feelings, and respect public opinion on governance. So, downward political accountability should be realized through elections so that leaders always have the sense of threat. If they don’t do the right thing, they won’t be elected.

The second issue is no longer existent in the current Chinese system, yet deserves attention. That is the “bad emperor” issue in traditional Chinese history. Undoubtedly, if you have competent and well-trained bureaucrats, or well-educated technical professionals who are dedicated to public interest, this kind of government is better than democratic government in the short term. Having a good emperor doesn’t guarantee no bad emperors will emerge. There is no accountability system to remove the bad emperor if there is one. How can you get a good emperor? How can you make sure good emperors will reproduce themselves generation after generation? There is no ready answer.

There is another problem of the economic model. The export-oriented model is good for China as long as China is a small economy. It is a great system to catch up with industrialized countries. Now China is the second largest economy in the world the export-oriented model simply cannot continue.

We know that the economic model based on consumer debt in the US and Europe is also not sustainable. This has proven to be true in the current financial crisis. There are other problems down the road. The Chinese system is heavily reliant on “financial repression”—in other words, high savings. However this fails to maximize market efficiency. So I think it is necessary to review this economic model in the long run.

The last point I want to make is morals. I think governments should do more than have the right economic policies. Even if a government can provide long-term economic growth, this is by no means its ultimate goal. The government has a moral requirement. Even if one system can provide material wealth to the citizens, if citizens cannot participate in wealth allocation or cannot get sufficient respect, problems will emerge. In the Middle East this Spring, we have seen a series of uprisings against authoritarian governments. This, to a large extent, is because people demand dignity. In the end I don’t think success belongs to only one model or the other. I am probably the first person to recognize that the US democratic system actually has a lot of problems that we have yet to solve.

Zhang Weiwei

ZHANG | In his presentation, Dr. Fukuyama raised four issues concerning the China Model, namely, accountability, rule of law, the “bad emperor” and sustainability. I would like to respond to Dr. Fukuyama’s view. I think what China has been doing is very interesting. China is now perhaps the world’s largest laboratory of political, economic, social and legal reforms in the world. What Dr. Fukuyama said reminds me of my conversation with the editor-in-chief of the German magazine Die Zeit last February. The topic was also the China Model. After a recent visit to Shanghai, he felt that there were more and more similarities between Shanghai and New York. In his eyes, China seems to follow the US model. “Does it mean there is no China Model but only the US model?” he asked. I counseled him to look at Shanghai more carefully and know the city well. A careful observer will find that Shanghai has overtaken New York in many respects.

Shanghai outperforms New York in terms of “hardware” such as high-speed trains, subways, airports, harbors and many commercial facilities, but also in terms of “software.” For instance, life expectancy in Shanghai is three to four years longer than New York, and the infant mortality rate in Shanghai is lower than New York. Shanghai is a much safer place where girls can stroll the streets at midnight. My message to this German scholar is that we’ve learned a lot from the West; we’re still learning from the West, and will continue to do so in the future, but it’s also true that we have indeed looked beyond the Western model or the US model. To a certain extent, we are exploring the political, economic, social and legal systems of the next generation. In this process, the more developed regions of China like Shanghai are taking the lead. Now I would like to share my views on Prof. Fukuyama’s doubts over the China Model.

First, with regard to accountability, what Prof. Fukuyama has discussed is the multi-party parliamentary democracy in the West. Having lived in the West for over two decades, I feel more than ever that this political accountability is hardly effective. Frankly speaking, from my point of view, the American political system is rooted in the pre-industrialization era, and the need for political reform in the US is as strong as in China, if not more. The separation of powers within the political domain alone can no longer effectively address the major problems in American society today; it certainly failed to prevent the recent financial crisis. To my mind, a modern society may need new types of checks and balances. It needs a balance between political, social and capital powers beyond the political domain. The separation of powers in the US has its weakness. As Prof. Fukuyama said, many vested interest groups, such as the so-called military-industrial complex, will never have their interests encroached upon, thus blocking many reform initiatives that are necessary for the US.

I think the accountability that the Chinese are exploring covers far wider areas than in the US. China’s experiment in this regard covers a whole range of economic, political and legal accountabilities. For example, our governments at all levels have the mission of promoting economic growth and job creation. An official cannot be promoted unless this mission is fulfilled. I read an article by Paul Krugman, the Nobel Laureate in economics, in which he said that economic growth and job creation were zero in the past decade in the US. There is no place in China, any province, city or county, in the past two decades that has ever registered such a poor record. On the contrary, economic performance across China is impressive. This is attributable to the Chinese practice of economic accountability. Of course, we have our own problems.

It is the same case with political and legal accountability. For example we are now having our dialogue here in the Jing’an District of Shanghai, which is one of the best districts in Shanghai. There was a fire accident last year that burned down a residential building in this district. As a result, twenty or so government officials and corporate executives were punished for their negligence of duty or malpractice. Such is the reality of China’s political and legal accountability.

In contrast, the financial crisis in the US has made American citizens lose one-fifth to one-quarter of their assets. Yet, three years have passed and nobody in the US has been held accountable politically, economically or legally. To make things worse, those financiers who are perhaps the culprits of the financial crisis are financially rewarded in tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. However furious the American public and President Obama are, the bonuses are still awarded to them according to the contracts they signed in the name of rule of law.

This reminds me of the second issue concerning rule of law in the China Model raised by Prof. Fukuyama. We are promoting the rule of law in China, though there is indeed huge room for improvement. But I think some elements in our traditional philosophy remain valid and relevant. For example, there is the traditional concept of “tian” or “heaven,” which means the core interest and conscience of the Chinese society. This can by no means be violated. Laws may be applied strictly to 99.9% cases in China, but we maintain a small space where political solutions, within the framework of rule of law, are applied when “tian” or the core interest and conscience of the society are violated. In other words, the above-mentioned Wall Street bonus issue would not happen in China. So we try to strike a balance between rule of law and “tian,” and this is what China wants to do in its exploration of the legal regime of the next generation. Otherwise it is very likely to fall prey to what’s called fatiaozhuyi or excessive legalism, which could be very costly for a huge and complex society like China.

As for the “bad emperor” issue, it has been solved. To say the least, my rough estimate is that even during the times of “good and bad emperors” in China’s long history, there were at least seven dynasties which were longer than 250 years, in other words, longer than the entire history of the US. In fact, the entire contemporary history of the West is only about two to three hundred years and this history has witnessed slavery, fascism, tons of conflicts and two World Wars.

In my view, China’s political institutional innovation has solved the issue of the “bad emperor.” First and foremost, China’s top leadership is selected on merits, not heredity. Second, the term of office is strict and top leaders serve a maximum of two terms. Third, collective leadership is practiced, which means no single leader can prevail if he deviates too much from the group consensus. Last but not the least, meritocracy-based selection is a time-honored tradition in China, and top-level decision makers or the members of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China, are selected with a criteria that usually requires two terms as provincial governors or ministers.

As you know, it is by no means easy to govern a Chinese province, which is usually the size of four to five European countries. This system may have its weakness, but one can be certain that with this system of meritocracy it is highly unlikely that China will elect a national leader as incompetent as George W. Bush or Naoto Kan of Japan. In fact, what concerns me now is not the “bad emperor” issue in China, rather it’s the “George W. Bush” issue in the US.

If the American political system continues as it is today, I am really concerned that the next elected US president could be even less competent than George W. Bush. As a superpower, American policies have global implications. So the lack of political leadership or accountability in the US could cause serious problems. I would like to have Prof. Fukuyama’s view on the “George W. Bush” issue. Bush did not run his country well and the US declined sharply for eight years running. Even a country like the US cannot afford another eight years of further decline.

With regard to the sustainability of the China Model, in my new book The China Wave, I put forward the concept of China as a unique civilizational state, which has its own logic and cycles of development, and the idea of “dynasties” is helpful here. A good dynasty in China tends to last two to three hundred years and more, and this logic has been observed in the past four thousand years. From this perspective, China now is still at the early stage of its current upward cycle. This is one reason why I am optimistic about the future of China.

My optimism also comes from the Chinese concept of shi or overall trend, which is hard to reverse once taking hold. The course of development took a sharp turn in Japan thanks to the Meiji Restoration in the late 19th century while China didn’t manage to do it due to China’s strong internal inertia, which is a negative way of saying shi. Now a new shi or overall trend has taken hold and gained a strong momentum after the three-decade-long reform and opening-up. This overall trend can hardly be reversed despite the fact that some waves may go in the opposite direction. It is the shi that defines the general trend of China’s big cycles. Unfortunately many Western scholars fail to understand that, and their pessimistic predictions about China’s collapse have lasted for about two decades. Instead of China’s collapse, these predictions have “collapsed.” Some Chinese within China still hold this pessimistic view. But I think this view will also “collapse,” and that won’t take another twenty years.

Prof. Fukuyama mentioned the trade dependency of the China Model. China indeed depends a lot on foreign trade, but this dependency has been somewhat inflated. Foreign trade takes a large share of GDP if calculated on the official exchange rate. But foreign trade is calculated in US dollars, and the rest of the GDP is calculated in the undervalued RMB. As a result, from my point of view, there is an exaggerated high trade dependency.

Looking ahead, China’s domestic demand may well become the world’s largest. China’s urbanization didn’t gather pace until 1998. From now on, there will be 15-25 million new urban dwellers every year in China. This unprecedented scale of urbanization in human history will create immense domestic demand, which may be larger than the combined demands of all the developed countries in the future.

In terms of respecting individual values, I don’t think there is a huge difference between China and the rest of the world. The end is the same, which is to respect and protect individual values and rights. But the difference lies in the means to achieve the end. China has a holistic tradition in contrast to the individualistic one in the West. The Chinese approach based on holistic tradition produces better results in promoting individual values and rights.

I describe the Chinese holistic approach as Deng Xiaoping’s approach and India’s individualistic approach as Mother Teresa’s approach. Deng Xiaoping’s approach has helped lift almost 400 million Chinese individuals out of poverty and fulfill their values and rights: they can watch color TVs, drive on highways and surf and blog on the Internet to comment on all kinds of issues. But in India, although Mother Teresa’s approach touched and moved countless individuals and she was even awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the overall picture of poverty in India remains largely unchanged.

I would also like to talk about public participation in the decision-making process. Actually I do hope that Prof. Fukuyama will have the opportunity to do more field research in China. What is the Chinese way of democratic decision-making? Let me share one example. In China, we make a national development plan every five years. This is the crystallization of tens of thousands of rounds of discussions and consultations at all levels of the Chinese state and society. In my opinion, this is the real democratic decision-making process, and it ensures quality decision making. The gap between the West and China in this regard is, to be frank, huge. To my mind, China is perhaps “at the graduate level” and the West perhaps at the “undergraduate” or even “high school level,” if this analogy fits.

The recent turmoil in the Middle East, at the first glance, is about the pursuit of freedom. But one of the root causes, to my mind, lies in the economy. I have been to Cairo four times. Twenty years ago, this city was about five years behind Shanghai. But now the difference is four decades. Half of the young generation is unemployed. Other than revolt, what else can they do?

My observations of the Middle East have led me to conclude that, while many in the West cheer the Arab Spring, don’t be too optimistic. I hope the region will do well, but it will be difficult, and the Arab Spring today may well turn into Arab Winter in the not too distant future with American interests undermined. The situation in this region is no better than that of China during the 1911 Revolution, which was followed by a long period of chaos. There remains a long journey to go in the Middle East. We shall wait and see what will happen.

.~`~.

II

Francis Fukuyama

Fukuyama | Let me respond one by one. First of all, when you are comparing political systems, I think you should distinguish policies and institutions. That is to say, the specific policies taken by certain leaders and the system as a whole. It is clear that American policy-makers have made a lot of mistakes, for example, the Iraq war for which we paid a big price. And the financial crisis which originated from Wall Street is the result of free market ideology, excessive household consumption and expansion in the property market. But policy mistakes can be made by any regime at any time. I don’t think democratic regimes are more prone to policy mistakes than authoritarian ones. In fact, the latter have even bigger troubles. The mistakes could drag on as the decision-makers cannot be removed. So the price at the end of the day will be very high.

You said that China will never select a national leader like George W. Bush. Well, it is a bit hard to say that. George W. Bush was the president only for eight years. If you go back to the “bad emperor” problem, the last bad emperor China had, quite frankly, was Mao Zedong. The damage during the Cultural Revolution upon the Chinese society was far more severe than anything George W. Bush did to American society.

You also mentioned several characteristics of the Chinese leadership. I do recognize the positive sides of collective leadership and the term limits for leaders in China. If Gaddafi or Mubarak had term limits, Libya and Egypt would not be in so much trouble.

You also said that consensus should be reached within the leadership in order to make important decisions. In my opinion, this practice is exactly a lesson learned from the Cultural Revolution. In the past, whims of one individual wreaked havoc upon the whole society. So the Communist Party had to create new institutions, which include term limits.

I want to give credit to the Chinese system. Many Americans fail to recognize the fact that, although China is an authoritarian country, it is also highly institutionalized and has checks and balances in its system. However I think we need to think about the long run.

The current institutional set-up within the Chinese Communist Party is based on the memory of those who lived through the Cultural Revolution. It is still not possible to talk about that part of the history fully in China. You are not teaching the younger generation what happened. They have not experienced the Cultural Revolution and tend to forget it. But the problem is what will happen if the new generation has no such experience and psychological scars from living under that kind of unconstrained dictatorship. Are they going to be willing to live with the current checks on the use of power?

That is why I believe the formal rule of law and checks and balances in the long run are viable because it is not just reliant on the memory of one generation. If the next generation doesn’t have the same memory, they might repeat the same mistakes. The rule of law and democracy are the means to maintain what is good at the moment and let it transcend generations.

In my new book, one of the things that I argue is that we all have a common human nature. That human nature makes us favor our families, friends, brothers, sisters and children. Giving our personal preference to friends and family is a natural mode of human social interaction. But we cannot base political systems on friends and families. So one of the greatest achievements of Chinese politics is to create a political system that is highly institutionalized beyond all friends and families, beyond kinship and personal relations.

So, in order to get into the civil service, you have to take exams. It is not just based on who is relatively influential. This system was fully institutionalized in the earlier Han Dynasty in the first century BC. But at the end of the late Han Dynasty in the third century, the political system was recaptured by elites, basically by families who had a lot of wealth and power. Then the period of Three Kingdoms was a very complicated period of Chinese history. Basically rich families recaptured power and the modern institutions based on meritocracy deteriorated. I think this could happen to any political system.

This is something I am worried about in the American system because we have elites who are very wealthy. They can take care of their children well and send them to very good schools. Of course this is not what is happening in China, but can be a threat in the Chinese system.

How do you make sure that elites who run the country remain based on merit and talent, as opposed to families and friends? I would say the Communist Party of China in the past few decades has done a very good job. However there is corruption in the whole system. People want to take care of their relatives, friends and children. I think one of the problems in a system without downward political accountability is sometimes it is hard to prevent the re-entry of these personal connections into the political system. That is a problem I don’t think has been really solved. But in the long run, in order to let the system perpetuate for two or three decades, I believe you need downward accountability to solve the problem. At least in a democratic system, if we make mistakes we can recover from them. Sometimes it takes quite a number of years.

Let me quickly talk about one observation about the US. We have experienced the financial crisis. As Professor Zhang said, nobody has been punished. I think that is terrible because we have not held accountable people who are responsible for the financial crisis. Why it happened is complicated. But I don’t think it has to do with our democratic political system. After all, in the 1930s we had an even bigger economic crisis and it led to the election of President Roosevelt and an entirely new welfare state and regulatory system. They took a lot of strong measures because people were angry about what had happened. So the system can produce real accountability in the face of big policy mistakes.

In some sense, I even think the problem in the last couple of years in the US is that this crisis was not big enough. So policy-makers actually, in a way, mitigated the crisis. So the political momentum that favors reform has been undermined. That is why we didn’t get adequate regulatory reform. But I don’t think our democratic system caused the current crisis.

Zhang Weiwei

ZHANG | Each country has ugly events or mistakes in its history, including China. The Cultural Revolution and Great Leap Forward are indeed tragedies. I have my own personal experience of the Cultural Revolution. But it is necessary to emphasize that no country is an exception. The US has a history of slavery and Indian massacres, and institutionalized racial discrimination lasted for over a century. Prof. Fukuyama thinks that mistakes are corrected by the American system itself. Likewise, the Cultural Revolution and Great Leap Forward have also been corrected by the Chinese system itself. The “bad emperor” issue has been solved by the Chinese system. Now it is unlikely that any single leader can reverse the institutional set-up because what has taken shape in China is a system of power transfer that combines selection with some kind of election. I think this hybrid model is probably better than the pure election in the West, especially from the perspective of exploring the next generation’s political system. What the West is practicing is increasingly an election system which I sometimes call “showbiz democracy” or “Hollywood democracy.” It’s more about showmanship than leadership. As long as the procedure is right, it doesn’t matter who is elected, whether a movie star or a professional athlete. Whereas, in the Chinese tradition of political governance, there is a very important idea: The country can only be run by people with talents and expertise selected on meritocracy. This is deeply rooted in the Chinese mind.

Prof. Fukuyama mentioned Chairman Mao. On the one hand, it’s true that he made serious mistakes. On the other hand, we should not neglect the fact that he is still widely respected in China, and this fact shows Mao must have done something right. It is not fair to deny his main achievements, which include, first, unifying a country as large as China; second, women’s liberation and third, land reform. Deng Xiaoping once said Chairman Mao’s achievements outweighed his mistakes by 70% to 30%. I myself heard him making this comment, and I think it’s a fair assessment. Perhaps this different perception of Mao has to do with the different cultural traditions: the Chinese have a tradition of political dynamics while the West has legal dynamics.

Thanks to the three-decade reform and opening-up, there has emerged a stable middle class. I divide the Chinese society into three layers of structure: upper, middle and lower. This structure can prevent large-scale extremism of the Mao era. Such extremism is still possible in countries like Egypt because of the lack of a middle layer. This is the structural reason why China is not likely to shift towards extremism.

With respect to corruption, I think we need to do what can be called “vertical” and “horizontal” comparisons. Corruption in China is serious and not all that easy to tackle. However reviewing world history, you will find that all major powers including the US experienced periods of rising corruption, which often coincided with the process of rapid modernization. As your teacher Samual Huntington observed, the fastest process of modernization is often accompanied by the fastest rising corruption. This is mainly due to the fact that the regulatory and supervisory regimes simply can not catch up with the growth of wealth and capital in times of rapid modernization. Eventually corruption in China will be tackled and solved through the establishment of better regulatory and supervisory institutions.

I have visited the US on many occasions and found that the definition of corruption matters a lot. In my new book, I put forward a concept of “corruption 2.0,” as the financial crisis has exposed many serious “corruption 2.0” issues. For instance, rating agencies gain profits through regulatory arbitrage by granting triple A’s to dubious financial products or institutions. I think this is corruption. But these issues are called “moral hazards” in the American legal system. I think the financial crisis can be better tackled if these problems are treated as corruption.

We can also make horizontal comparisons. I have visited more than one hundred countries. The reality is that no matter how much Chinese complain about corruption at home, it is much worse in other nations of comparable size, say, those with a population of 50 million and above, and at similar stage of development such as India, Ukraine, Pakistan, Brazil, Egypt and Russia. The evaluation of Transparency International echoes my view.

Furthermore, it’s necessary to look at such a large country as China in terms of regions. China’s developed regions are more immune to corruption. I once stayed in Italy as a visiting professor and visited Greece several times, and I think Shanghai is definitely less corrupt than Italy and Greece. In Southern Italy, even the Mafia has been de facto legalized through the democratic system. I first went to Greece more than 20 years ago when its fiscal deficit was high. Now Greece is bankrupt and needs assistance. I said to my Greek friend very frankly: “Twenty years ago, your Prime Minister was Papandreou. Twenty years later, your Prime Minister is still a Papandreou. Your politics seems to be a few families’ business and the Greek economy goes bankrupt as a result of excessively high welfare system and poor governance.” I joked once that we could send a team from Shanghai or Chongqing to help Greece with good governance. Indeed, whatever political system, be it a one party system, a multi-party system, or a no party system, it must all boil down to good governance and what you can deliver to your people. Therefore, good governance matters most, rather than western-style democratization.

This brings me to Prof. Fukuyama’s “end of history” thesis. I have not published my point of view yet. But mine is exactly the opposite to Prof. Fukuyama’s. I take the view that it is not the end of history, but the end of the end of history.

The Western democratic system might be only transitory in the long history of mankind. Why do I think so? Two thousand and five hundred years ago, some Greek city states like Athens, practiced democracy among its male citizens and later were defeated by Sparta. From then on, for over two thousand years, the word “democracy” basically carried the negative connotation, often equivalent to “mob politics.” The Western countries did not introduce one-person-one-vote system into their countries until their modernization process was completed.

But today, this kind of democratic system cannot solve the following big problems. First, there is no culture of “talent first.” Anyone who is elected can rule the country. This has become too costly and unaffordable even for a country like the US. Second, the welfare package can only go up, not down. Therefore it is impossible to launch such reforms as China did in its banking sector and state-owned enterprises. Thirdly, it is getting harder and harder to build social consensus within democratic countries. In the past, the winning party with 51% of votes could unite the whole society in the developed countries. Today American society is deeply divided and polarized. The losing party, instead of conceding defeat, continues to obstruct. Fourth, there is an issue of simple-minded populism which means that little consideration can be given to the long-term interest of a nation and society. Even countries like the US are running this risk.

In 1793, King George III of the UK sent his envoy to China to open bilateral trade. But Emperor Qianlong was so arrogant that he believed that China was the best country in the world. Therefore China did not need to learn anything from others. This is what defined the “end of history” then, and ever since China lagged behind. Now I observe a similar mindset in the West.

It is necessary to come to China and see with one’s own eyes how China has reformed itself over the past three decades. Small is each step, yet the journey is non-stop. The West still has strong faith in its own system, but it is the same system that has become more and more problematic. Greece, the cradle of Western democracy, has gone bankrupt. The British fiscal debt is as high as 90% of its GDP.

What about the US? I did a simple calculation. The 9/11 attack cost the US about $1 trillion, the two not-so-smart wars cost US about $3 trillion and the financial crisis about $8 trillion. Now the fiscal debts of the US are somewhere between $10 to 20 trillion. In other words, if the US dollar was not the main international reserve currency—this status may not last forever—the US would be bankrupt already.

The rise of China is what we call “shi” or an overall trend, the scale and speed of which is unprecedented in human history. My own feeling is that the Western system is trekking on a downward slope and in need of major repairs and reforms. Some Chinese always speak and think highly of the US model, but to someone who has lived in Europe and visited the US many times, this is a bit too simplistic and naive. One should be objective in comparing China and the Western countries. What are their strengths and weaknesses? What are our strengths and weaknesses, what is worthy of learning from the West or being mindful of? This is the right mindset.

.~`~.

III

Francis Fukuyama

Fukuyama | Again I want to say that you need to distinguish a political system from short-term policy. There is no question that the US, in the past generation, has had excessive borrowing. But I actually don’t think this is the problem of our democratic system.

Germany is very close to China. It is a large economy that has a consistent trade surplus and a relatively booming job market. At the same time, Germany has not been obsessed with the excessive financial innovation that brought down the US economy and caused the property bubble. It is a democratic country. It has just made choices different from the US. So I don’t think it has anything to do with whether this country is a democracy or not. Every country can make policy mistakes.

Again I want to put things into perspective. I really don’t want to belittle the great achievement that China has scored. However my point is that you cannot make long-term judgments according to short-term performance. Japan was unstoppable in the late 1980s before the burst of the Japanese property bubble. After the bubble burst and following policy mistakes, there has since been twenty years of economic stagnation and low growth. But people in the mid 1980s believed that Japan would grow larger and larger until it overtook the US. There was a belief of emerging Japanese supremacy. Now I think if you look at economic growth in a longer-term perspective, what is the bigger challenge for China is the same for any economy. There is at first a period of really rapid economic growth and industrialization that mobilizes people from the countryside to cities.

Europe grew rapidly at that stage, so did Korea and Japan. Perhaps 25 years ago, China entered this process. At a certain point, that transition got people out of the agricultural economy. Then you face the next challenge of productivity in a more mature economy. And I think it is probably a universal truth that no country has ever maintained double-digit growth up to that point where you have become an industrialized economy. That will happen to China as well.

The Chinese economy will slow in the next generation. All countries, in particular Asian countries, will face the problem because the birth rate is coming down, which is going to be a huge burden. The elderly population is large because of greater longevity and low infant mortality, not the one-child policy. This is true in Taiwan, Singapore and mainland China.

I attended a recent meeting where one of the economists said that in the year 2040 or 2050, China is going to have 400 million people over 60 years old. That is an enormous challenge that other developed countries face as well. So when we talk about the resilience of a political system, we have to think about the long term. Given the different upcoming challenges of falling birth rates and a much older population, how flexible can the system be? But I would not say democratic countries have all the answers. This is the challenge of everyone.

Professor Zhang also brought up the issue of populism, which means people do not always make right choices in democracies. I think there are many examples of this in American politics these days. Sometimes I have to shake my head because of some stupid decisions made by politicians. But Abraham Lincoln, I think the greatest president of the US, had a famous saying: “You can fool some of the people all of the time, all of the people some of the time, but you cannot fool all the people all of the time.” Particularly with the rise of education and income, I think this kind of populism in some respects has changed. This is a test of real democracy. Yes people in the short run make bad decisions or choose the wrong leaders. But in a mature democracy there is genuine freedom of expression and genuine ability to debate issues. In the long run, people will make the right decisions. I think in the history of the US we can point out many bad short-term decisions, but in the end people will come to understand their interests which will lead them to make the right decisions.

Winston Churchill, the great British Prime Minister, once said: “Democracy is the worst form of government except for all those others that have been tried.” I think it is important because the question is what you have as alternatives. The alternative is really high-quality authoritarian government, which I admit that China has had in the last generation. That may be a better system. But the question is how to guarantee that institution will guide the society to make the right decisions.

Professor Zhang also mentioned the rise of the middle class. He said that this rules out the possibility of populist extremism or insurgency.

One of my teachers was Samuel Huntington. He wrote a book in 1968 called Political Order in Changing Societies. One of the things that Samuel Huntington said is that revolutions are never created by poor people. They are actually created by the middle-class. They are created by people who are educated to have opportunities. But these opportunities are blocked by the political or economic system. It is the gap between their expectation and the ability of the system to accommodate their expectation that causes political instability. So the growth of middle class, I think, is not a guarantee against insurgencies, but a cause of insurgencies.

What happened in Egypt and Tunisian was the growth of a fairly large middle class, a lot of college graduates and a lot of people who use the Internet. Connected to the outside world, they were able to understand how bad their governments were.

In terms of the sustainable growth of China, I actually don’t think the source of China’s instability will come from the poor peasants in the countryside. Political revolutions are introduced by the educated middle class because the current political system prevents them from being connected with the larger outside world and doesn’t grant them the kind of social status that they deserve.

I know there are 6-7 million new college graduates every single year in China. One of the greatest challenges for stability is not the poor people in China, but whether the society is capable of meeting the expectations of the educated middle class.

In terms of corruption, I didn’t want to argue that democracies can better solve the question of corruption because obviously you have quite a few democracies with high levels of corruption. In many aspects, China may be less corrupt than many of these democratic countries. But I do think that one way of combating corruption is freedom of press where you have the ability to expose corruption without being concerned about possible coercion or threat. Granted, in democratic countries that is not always the case. For example, in Italy, the Prime Minister owns the whole media. But I do think it is an advantage to have freedom of speech whereby you actually can criticize those powerful people in the political hierarchy and don’t have to worry about personal retaliation. That is the advantage of having a liberal democratic system.

Zhang Weiwei

Zhang | Thank you, Prof. Fukuyama. You said that we should make evaluations in a longer timeframe. In 1985, I visited the US as an interpreter for a Chinese leader, and we met with Dr. Henry Kissinger. When he was asked to talk about Sino-US relations, he said he would rather listen to us first, because we came from a country of thousands of years of civilization. Of course this is a token of courtesy. However we should remember the fact that China was indeed a more advanced country than most in terms of national strength and its political system for most of the past 2000 years. I do want to give credit to Dr. Fukuyama, for what distinguishes him from many other Western scholars is that he has spent a lot of time and effort studying the political institutions of ancient China as evidenced by his observation that China established the world’s first modern state.

China lagged behind the West in the past two to three hundred years. But China is catching up fast, particularly in the more developed regions of China. I am afraid that the West is a bit too arrogant and fails to look at China with an open mind. To my mind, the West can already learn something from China. President Obama may be right, as he urged the US to build high-speed railways, focus on basic education, reduce fiscal deficits, have more savings, develop the manufacturing industry and ramp up the export sector. He has emphasized that the US cannot become the world’s No. 2. It is very obvious that he feels the pressure from the rise of China.

Prof. Fukuyama sounds optimistic on the issue of populism. He has great faith in the US that it can learn from its own mistakes, rather than being led by populism. But I tend to take the view that populism seems to have become even more widespread in the world today thanks to the modern media. Now a country or society in fact may crash overnight because of excessive populism, and this is more than an issue of political institutions.

In China, its thousands of years of traditions leave their marks on everything. I am not saying tradition is always good or bad. My point is that it is impossible or unrealistic to break away from one’s tradition as it always has an imprint on what we are doing today. Therefore I always say that like it or not, the Chinese characteristics are with us all the time because the Chinese historical genes are with us. What we can do is to leverage advantages of our traditions while avoiding whatever disadvantages of our traditions. What happened in the Cultural Revolution tells us that it is very difficult to break away from one’s tradition. China does have some very good traditions which include belief in meritocracy, so selection plus some form of election offers a promising future in China, and we can do well in this regard, given our thousands of years of experience in meritocracy-based selection.

Prof. Fukuyama talked about alternatives to democracy. This is exactly an area where our views differ. China does not have the intention to market its model as alternative for other peoples or countries. What we focus on is simply running our own country well, which means doing a good job for one-fifth of mankind, and nothing is better than achieving this goal. But it is also true that if you do well, others will follow your example. Today virtually all of China’s neighboring countries, from Russia to India, from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia to the Central Asian nations are learning in one way or another from the China Model.

Professor Huntington’s view of the conflict between the middle class and the state is shared by most Western and some Chinese scholars who advocate an independent civil society. But China has its own long cultural traditions, which may impact China’s middle class in a different way. Most Westerners view government as a “necessary evil,” but most Chinese view government as a “necessary virtue.” With this cultural legacy, the Chinese middle class is more likely to become the staunchest supporter of China’s stability in the world. In addition, instead of being confrontational, the relationship between the middle class and the Chinese state is most likely to be positively interactive, rather than confrontational. This will generate a social cohesion in the Chinese society unmatched in any Western society.

Now I would like to talk about the issue of corruption. We all know Asia’s four Little Dragons: South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong. After their modernization process was largely completed, Taiwan and South Korea adopted the Western political system while Singapore and Hong Kong chose to stay more or less the same course. Look at the situation today: Hong Kong and Singapore are much less corrupt than South Korea and Taiwan, as acknowledged by all those who study corruption. Hong Kong used to be very corrupt in the 1960s, but this problem was successfully tackled by setting up the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC). In other words, the Western democratic system is by no means the best solution to the issue of corruption, at least in the non-Western world.

Transparency International’s corruption indicators show that most non-Western “democracies” with a population of 50 million and above are faced with more corruption at home than China. As a matter of fact, corruption has become even worse in Taiwan after it became a democracy. Otherwise Taiwan’s leader Chen Shui-bian would not end up in jail. South Korea’s five elected presidents were all implicated one after another in corruption scandals. In contrast, Hong Kong and Singapore, without adopting the Western political model, have succeeded in sharply reducing corruption through rule of law and institutional innovation.

As for Churchill’s remark about democracy, some Chinese re-phrased his remark into “democracy is the least bad system,” and I checked the context of his remark and found that he made it in a Westminster debate in 1947. He was clearly referring to the Western democracy as practiced in the West. Winston Churchill himself was firmly opposed to India’s independence. How could he be expected to support India’s adoption of Western-style democracy? But I myself have borrowed Winston Churchill’s phrase and described the China Model as the “least bad model,” which means it has its weaknesses, but it has performed better than other models.

.~`~.

IV

Francis Fukuyama

Fukuyama | Let me start with the question of the middle class. Is the Chinese middle class different from the middle class of the non-Chinese societies? This is actually a question that I debated a lot with Professor Huntington. He wrote a book entitled Clash of Civilizations in 1990, in which he basically made the argument that culture determines behavior. Despite the changes brought by modernization, he argued, culture still determines people’s behavior even though they are more modern.

I believe culture is very important. The reason that I study international politics is that I like observing people who are different from myself. So cultural diversity is the reality and it is good that not everybody is the same. But one of the larger questions is whether culture really projects itself across time in a way that resists the process of political, social and economic development or whether the process of modernization leads to cultural convergence.

Let me give you one example. Look around the room in which there are a lot of women sitting. Why are there a lot of women in the audience? In traditional times, the status of women was low in the societies where inheritance usually went to the male line and opportunities for women were very limited. This was true in the US and Europe at their early stage of development. But when you travel around the developed world and here in East Asia, you see women everywhere. Why is that the case? Why have women’s status been raised? Why are they working in offices and factories? Why do they enjoy equal economic and social rights with men? The reason is the process of modernization. Today you cannot run a modern economy without women in the labor force.

Saudi Arabia doesn’t allow women to drive. So they have to employ around half a million chauffeurs from South Asia simply to drive their women around. If they didn’t have oil, this is probably the most insane economic system you could possibly imagine. Despite what Muslim culture says about the appropriate roles of women, women in the Middle East are getting more powerful and more politically organized. They are demanding equal rights with men. This seems to me a case where different cultures are coming up with similar solutions to the problem of the status of women. It happens not because culture is determinant, but because the modernization process forces societies to come up with solutions.

I don’t think you can have a modern society without granting equal rights to women. Of course this is an open question. Professor Zhang said that middle-class people who are educated, relatively secure and have private property are going to be different from middle-class people elsewhere because they live in a Chinese cultural system. Maybe that is the case.

But from my observation, middle-class people in different cultures actually behave in a similar way. In the Arab world, people think the Arabian people are different because of the influence of Islam. Yet through the past year the Arab people have been on the street to demonstrate against their governments. So I think that some of the assumptions about the role of culture may not be right. Maybe culture did dictate some behavior in the past. But under current conditions, it is different. With the Internet or travel, maybe people’s behavior is determined more by the needs and aspirations of the current generation than the weighty traditions of the past.

Let me say just one final thing on which I agree with Professor Zhang. I do think that there is a failure among the people in the US and Europe to appreciate Chinese achievement, both the contemporary and historical achievement. My recent book has six chapters out of which three are on China. There are more chapters on China than other parts of the world. I really spent a lot of time trying to teach myself as much Chinese history as I could. Recognizing the strength of that history is important for American and also for Chinese.

No civilization can live on borrowed values and institutions. What I perceive is going on right now in China is an attempt to recover authentic Chinese roots. I think this is a good thing that China has to do. The challenge is to recover that pride in history and tradition and make it compatible with modern institutions. We should do it in a way that doesn’t lead to nationalism or narrow chauvinism.

What is a modern Japan like? It is not similar with the US, UK or France. It has rich Japanese characteristics. I think a modern China needs to have very Chinese characteristics as well. So it is going to be a very important task to figure out what are typical Chinese characteristics and what is required of a modern society. That is also part of a larger international order. Only in this way can we live with others peacefully.

Zhang Weiwei

ZHANG | Many Western political scientists take the view that modernization leads to cultural convergence. But experience proves that it is not necessarily true. Let’s take China as an example. The Chinese are known to be busy with modernization, creating wealth and making money. But a few years ago, a song became an instant national hit that encouraged people to visit their parents more often. This song is heart-warming to most Chinese and it struck the chord of public sentiment. In other words, despite the rapid pace of modernization and the rise of individualism, at the core of the Chinese tradition is still family, for which most Chinese are willing to sacrifice much more than most Westerners.

The very essence of a culture is unlikely to be changed and shall not be changed by modernization. Otherwise the world would become too boring. How can it be possible to change the essence of a culture as strong as China’s? One is the McDonald’s culture, and the other is China’s Eight-Schools-of-Cuisine culture, and they are immensely different. Indeed, the former has no power to conquer the latter. Rather, the latter may be able to assimilate the former. I appreciate the views of Edmund Burke, the British political philosopher of the 19th century, who held that any change in a political system must be derived mainly from a nation’s own traditions.

Furthermore, I think, the main reason for respecting culture is our respect for the wisdom associated with culture. Wisdom and knowledge are two different things. We have far more knowledge today than anytime in the past. Our school kids today may have more knowledge than Confucius or Socrates. However human wisdom has hardly grown. Here I have a simple suggestion, which I’m not sure if Prof. Fukuyama will accept: in addition to the three elements of a modern political institution he has mentioned, namely, state, accountability and rule of law, we could add one more element—wisdom. The US has won many wars tactically, but lost them strategically, as the wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq, to name just a few, attest. This situation has to do with wisdom, and I think the importance of wisdom can hardly be overemphasized.

I was recently in Germany giving a lecture. One German economist told me a story. German Chancellor Angela Merkel asked a German economist why there are no first-class economists or Nobel laureates in economics in Germany. This economist replied, “Mme Chancellor, please don’t worry about this at all, because if there were first-class economists, there would be no first-class economy.” In other words, it’s economics that is in trouble. Among all social sciences invented in the West, I think economics is arguably the closest to the truth because it is more like natural sciences and supported by mathematical models. With this in mind, frankly speaking, political science and other social sciences invented in the West may well be further away from the truth than economics. This is why we should be bolder in our thinking and more courageous in our efforts toward innovative discourse.

I share one commonality with Prof. Fukuyama. We are both trying to work out of the box of the Western political science, and his new book tries to integrate anthropology, sociology, economics, archeology and more. His efforts merit our recognition and respect, though I don’t agree with him on everything. On our part, my colleagues and I are indeed moving a bit further than Prof. Fukuyama and we are questioning the whole range of the Western political discourse. But our intention is not to score political points or to prove how good China is or how bad the West is, or vice versa. Rather we try to find new ways to address such global challenges as poverty alleviation, the clash of civilizations, climate change and various problems associated with urbanization. Western wisdom is indeed insufficient. Chinese wisdom should make its contributions.

Francis Fukuyama is a Olivier Nomellini Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Standard University, and the author of The End of History and The Last Man and the Origins of Political Order.

Zhang Weiwei is a professor at the Geneva School of Diplomacy and International Relations, a senior fellow at the Chunqiu Institute and a guest professor at Fudan University, China. He is the author of The China Wave: the Rise of a Civilizational State.

.~`~.

Για περαιτέρω ιχνηλάτηση και πληρέστερη προοπτική

*