.

.~`~.

Ι

Το τέλος τής χριστιανοδημοκρατίας

Τι σημαίνει για την Ευρώπη η πτώση τού κινήματος

Η σημερινή Ευρώπη είναι μια δημιουργία των χριστιανοδημοκρατών. Ωστόσο, τόσο ως ένα σύνολο ιδεών όσο και ως πολιτικό κίνημα, η Χριστιανική δημοκρατία αποκτά όλο και λιγότερη επιρροή και γίνεται λιγότερο συνεκτική. Καθώς το μεγαλύτερο εγχείρημα της ευρωπαϊκής ολοκλήρωσης αντιμετωπίζει νέους κινδύνους, λοιπόν, ο πιο σημαντικός υποστηρικτής της μπορεί σύντομα να αποδειχθεί ανίκανος να την υπερασπιστεί.

*

Η σημερινή Ευρώπη είναι μια δημιουργία των χριστιανοδημοκρατών. Αυτοί ήταν οι αρχιτέκτονες της ευρωπαϊκής ολοκλήρωσης και του μεταπολεμικού ατλαντισμού. Και ήταν καθοριστικής σημασίας για την δόμηση της μορφής τής συνταγματικής δημοκρατίας που επικράτησε στο δυτικό μισό τής ηπείρου μετά το 1945 και έχει σταθερά επεκταθεί ανατολικά από τότε που έπεσε το Τείχος τού Βερολίνου το 1989. Η πιο ισχυρή πολιτικός τής Ευρώπης, η Γερμανίδα καγκελάριος Άνγκελα Μέρκελ, είναι μια χριστιανοδημοκράτις, όπως είναι ο πρόεδρος της Ευρωπαϊκής Επιτροπής, José Manuel Barroso, και ο διάδοχός του, ο Jean-Claude Juncker. Στις εκλογές για το Ευρωπαϊκό Κοινοβούλιο τον περασμένο Μάιο, η ηπειρωτική ένωση των Χριστιανοδημοκρατικών κομμάτων - το Ευρωπαϊκό Λαϊκό Κόμμα (ΕΛΚ) - κέρδισε τις περισσότερες έδρες.

Ωστόσο, τόσο ως ένα σύνολο ιδεών όσο και ως πολιτικό κίνημα, η Χριστιανική δημοκρατία αποκτά όλο και λιγότερη επιρροή και γίνεται λιγότερο συνεκτική κατά τα τελευταία χρόνια. Η πτώση αυτή δεν οφείλεται μόνο

στην κοσμική στροφή τής ηπείρου. Τουλάχιστον εξίσου σημαντικά είναι τα γεγονότα ότι ο εθνικισμός - ένας από τους πρωταρχικούς ιδεολογικούς εχθρούς των Χριστιανοδημοκρατών - βρίσκεται σε άνοδο και ότι το βασικό εκλογικό σώμα τού κινήματος, ένας συνασπισμός ψηφοφόρων από την μεσαία τάξη και τους αγρότες, συρρικνώνεται. Καθώς το μέγα εγχείρημα της ευρωπαϊκής ολοκλήρωσης αντιμετωπίζει νέους κινδύνους, λοιπόν, ο πιο σημαντικός υποστηρικτής της μπορεί σύντομα να αποδειχθεί ανίκανος να την υπερασπιστεί.

Παλαιά Θρησκεία

«Χριστιανοδημοκράτης» είναι μια ονομασία που ακούγεται περίεργη στον οποιονδήποτε έχει συνηθίσει σε έναν αυστηρό διαχωρισμό εκκλησίας και κράτους. Ο όρος εμφανίστηκε για πρώτη φορά στον απόηχο της Γαλλικής Επανάστασης και εν μέσω σκληρών μαχών για την τύχη τής Καθολικής Εκκλησίας μέσα σε μια δημοκρατία. Για το μεγαλύτερο μέρος τού δέκατου ένατου αιώνα, το Βατικανό έβλεπε τις σύγχρονες πολιτικές ιδέες – συμπεριλαμβανομένης της φιλελεύθερης δημοκρατίας - ως μια άμεση απειλή για τα κεντρικά δόγματά του. Αλλά υπήρχαν και καθολικοί στοχαστές οι οποίοι συμφώνησαν με την διορατικότητα του Γάλλου συγγραφέα Alexis de Tocqueville ότι, είτε μας αρέσει είτε όχι, ο θρίαμβος της δημοκρατίας στον σύγχρονο κόσμο ήταν αναπόφευκτος. Οι λεγόμενοι Καθολικοί φιλελεύθεροι προσπάθησαν να κάνουν την δημοκρατία ασφαλή για την θρησκεία με τον κατάλληλο εκχριστιανισμό των μαζών: Στο κάτω-κάτω, έλεγε το σκεπτικό, μια δημοκρατία με θεοσεβείς πολίτες θα έχει πολύ καλύτερες πιθανότητες επιτυχίας από μια δημοκρατία που οι πολίτες της θα ήταν κοσμικοί. Άλλοι Καθολικοί διανοούμενοι ήλπιζαν να κρατήσουν τους ανθρώπους σε τάξη μέσω Χριστιανικών θεσμών, και ιδίως τον παπισμό, τον οποίο ο Γάλλος στοχαστής Joseph de Maistre έβλεπε ως μέρος ενός πανευρωπαϊκού συστήματος ελέγχων και ισορροπιών.

Το πιο σημαντικό, κατά τα τέλη τού δέκατου ένατου και στις αρχές τού εικοστού αιώνα, το ίδιο το Βατικανό τελικά έφθασε να δει τα οφέλη τού να παίζει το δημοκρατικό παιχνίδι και να προωθεί κόμματα που θα υπερασπιστούν τις ανησυχίες τής εκκλησίας. Αρχικά, το έπραξαν με κακή πίστη – τα χριστιανοδημοκρατικά κόμματα ουσιαστικά λειτούργησαν ως ομάδες συμφερόντων μέσα σε ένα σύστημα του οποίου τη νομιμότητα η εκκλησία συνέχισε να απορρίπτει. Με την χρήση τού όρου «δημοκράτης», δεν σηματοδοτούσαν την αποδοχή τής αντιπροσωπευτικής δημοκρατίας, αλλά, μάλλον, την φιλοδοξία τους να συνεργαστούν με τους απλούς ανθρώπους. Μέχρι σήμερα, η προσέγγιση αυτή είναι εμφανής στην ανάδειξη όρων όπως «λαϊκό» ή «λαός» στα επίσημα ονόματα των χριστιανοδημοκρατικών κομμάτων.

Τα κόμματα έγιναν ισχυρότερα στις χώρες όπου η εκκλησία και το κράτος ήταν ομοιόμορφα ταιριασμένοι. Δεν υπήρχε ανάγκη για χριστιανοδημοκρατία σε μια βαθιά καθολική χώρα, για παράδειγμα στην Ιρλανδία, αλλά επίσης απέτυχε να ριζώσει στην Γαλλία, όπου οι Καθολικοί, αντιμετωπίζοντας επιθέσεις από τις αντικληρικές δημοκρατικές κυβερνήσεις, προσπάθησαν την πλήρη αλλαγή καθεστώτος. Αντιθέτως, εκεί όπου οι πολιτιστικοί πόλεμοι μεταξύ κοσμικών δυνάμεων και εκκλησίας ήταν έντονοι, αλλά τελικά οδήγησαν σε αδιέξοδο, όπως στην Γερμανία και στις λεγόμενες χώρες Μπενελούξ (Βέλγιο, Ολλανδία και Λουξεμβούργο), οι Καθολικοί επένδυσαν στην δόμηση κομμάτων.

Όπως έχει καταδείξει ο πολιτικός επιστήμονας Στάθης Καλύβας, οι ηγέτες των χριστιανοδημοκρατικών κομμάτων τελικώς ανέπτυξαν τα δικά τους συμφέροντα. Η εμπλοκή στο δημοκρατικό παιχνίδι έφερε οφέλη και πόρους - και οι Χριστιανοδημοκράτες αποδέχθηκαν τελικά την πολιτική συμμετοχή ως νομιμοποιημένη. Μετά τον Δεύτερο Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο, όταν η δημοκρατία σάρωσε την Ευρώπη, το Βατικανό υποχώρησε κάπως: Έχοντας απορρίψει εντελώς το ιταλικό έθνος-κράτος και έχοντας απαγορεύσει στους Καθολικούς να παίξουν οποιονδήποτε ρόλο σε αυτό (ακόμη και με την απαγόρευση ψήφου), ο Πάπας υποστήριξε ένα νέο κόμμα που ονομάστηκε Popolari. Με το να ενώσει τους αγρότες και τα μικροαστικά στρώματα, το Popolari έγινε το δεύτερο μεγαλύτερο κόμμα στην χώρα μετά τους σοσιαλιστές.

Κατά την διάρκεια του Μεσοπολέμου, οι σχέσεις μεταξύ των χριστιανοδημοκρατών και της Αγίας Έδρας ψυχράνθηκαν σε ολόκληρη την Ευρώπη. Το Βατικανό είδε τα κόμματα που μπορούσε να ελέγξει ως χρήσιμα, αλλά περιθωριοποίησε αυτά που ήταν απρόθυμα να ακολουθήσουν τις οδηγίες από την Ρώμη και αντί με αυτά ασχολήθηκε κατευθείαν με τα κράτη. Προς τούτο, το Βατικανό εγκατέλειψε κόμματα όπως το Popolari και συνήψε ορισμένες διπλωματικές συμφωνίες που αποσκοπούσαν στην προστασία των συμφερόντων των Καθολικών - η πιο διαβόητη από τις οποίες ήταν η λεγόμενη Reichskonkordat ανάμεσα στον Χίτλερ και τον καρδινάλιο Eugenio Pacelli, ο οποίος αργότερα έγινε ο πάπας Πίος ΧΙΙ , τον Ιούλιο του 1933.

Δεν ήταν παρά μετά τον Δεύτερο Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο που τα χριστιανοδημοκρατικά κόμματα ελευθέρωσαν τον εαυτό τους πλήρως από το Βατικανό και ανέλαβαν ηγετικό ρόλο στην οικοδόμηση της μεταπολεμικής ευρωπαϊκής τάξης. Οι περιστάσεις δεν θα μπορούσε να ήταν πιο ευνοϊκές. Ο φασισμός και ο πόλεμος είχαν απαξιώσει τα ανταγωνιστικά κινήματα από την δεξιά. Και οι χριστιανοδημοκράτες είχαν θεωρηθεί ως η πεμπτουσία των ατλαντικών και αντικομμουνιστικών κομμάτων σε χώρες όπως η Ιταλία, η Δυτική Γερμανία, και άλλες όμορες χώρες τού Ψυχρού Πολέμου. Επιπροσθέτως, πλέον ενέκριναν την δημοκρατία, αν και με μια προειδοποίηση: Για να αποφευχθεί η διολίσθηση προς τον ολοκληρωτισμό, όπως ισχυρίστηκαν, οι δημοκρατικές κυβερνήσεις όφειλαν να έχουν πνευματικά ερείσματα - κάτι που παρεχόταν με τον καλύτερο τρόπο από την εκκλησία. Υπ’ αυτήν την έννοια, οι χριστιανοδημοκράτες απέρριψαν τόσο τον κομμουνισμό όσο και τον φιλελευθερισμό ως μορφές τού υλισμού. Αυτή η στάση δεν τους εμπόδισε τελικά από το να κάνουν ειρήνη με τον καπιταλισμό - ενώ επέμεναν ότι η θρησκεία ήταν επίσης αναγκαία για να κρατήσει υπό έλεγχο τα δεινά τής αγοράς.

Κόμματα, όπως η γερμανική Χριστιανοδημοκρατική Ένωση βγήκαν από την γραμμή τους για να συμπεριλάβουν τους Προτεστάντες –τερματίζοντας έτσι αιώνες θρησκευτικής σύγκρουσης. Στην πραγματικότητα, προσπάθησαν να γίνουν όσο το δυνατόν πιο συμμετοχικά, αντί να εμφανίζονται ως εκπρόσωποι θρησκειών (σεχτών). Το «σήμα κατατεθέν» τους ήταν μια κεντρώα πολιτική τής συναίνεσης και της διευθέτησης, στην βάση τής Καθολικής εικόνας μιας αρμονικής κοινωνίας, στην οποία ακόμη και το κεφάλαιο και η εργασία θα μπορούσαν να συνεργαστούν και η εκκλησία θα μπορούσε να διαδραματίσει έναν καίριο ρόλο στην παροχή κοινωνικών υπηρεσιών. Ωστόσο, εκείνη την χρονική στιγμή, οι παρατηρητές έλεγαν για τον Καθολικισμό αυτά που πολλοί Ευρωπαίοι λένε σήμερα για το Ισλάμ: Ότι ήταν εγγενώς ανελεύθερος και, ως ένα είδος μοναρχίας με έναν βασιλιά στη Ρώμη, ήταν ανίκανος να αποδεχθεί πραγματικά την δημοκρατία. Ο ιστορικός τού Χάρβαρντ, H. Stuart Hughes, για παράδειγμα, έγραψε το 1958, «Ένας χριστιανοδημοκράτης είναι κυρίως ένας χριστιανικός, και δημοκράτης μόνο σε μια ιεραρχική σχέση. Το επίθετο είναι πιο σημαντικό από όσο το ουσιαστικό».

Ωστόσο, οι χριστιανοδημοκράτες συνέχισαν να διαψεύδουν τους επικριτές τους. Στην Γερμανία, την Ιταλία, και - σε μικρότερο βαθμό - την Γαλλία, δημιούργησαν γνήσιες δημοκρατίες. Την ίδια στιγμή, όμως, κυβέρνησαν με κάμποση δυσπιστία προς την λαϊκή κυριαρχία. Ουσιαστικά προσπάθησαν να περιορίσουν τους ανθρώπους μέσω θεσμών όπως τα συνταγματικά δικαστήρια, να τους κάνουν πιο ηθικούς μέσα από τις διδασκαλίες τής εκκλησίας, για να τους υποβάλλουν σε μια νέα υπερεθνική τάξη: Η Ευρωπαϊκή Σύμβαση των Δικαιωμάτων του Ανθρώπου, για παράδειγμα, ήταν δημιούργημα των Βρετανών Συντηρητικών και των ηπειρωτικών χριστιανοδημοκρατών. Και ήταν οι τελευταίοι που έγιναν, επίσης, οι αρχιτέκτονες αυτού που σήμερα είναι γνωστό ως Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση. Στο κάτω-κάτω, οι χριστιανοδημοκράτες - όπως και οι Καθολικοί, διεθνιστές από την φύση τους - έδωσαν μικρή αξία στο έθνος-κράτος. Στην πραγματικότητα, κατά τον δέκατο ένατο αιώνα, υπήρχαν πρόσφατα ενοποιημένα έθνη-κράτη, όπως η Γερμανία και η Ιταλία, που είχαν εξαπολύσει τους λεγόμενους πολιτισμικούς πολέμους (που έμελλαν να γίνουν γνωστοί ως οι Kulturkampf τού Ότο φον Μπίσμαρκ) εναντίον Καθολικών, οι οποίοι θεωρήθηκαν ύποπτοι ότι έθεταν την πίστη τους προς το Βατικανό πάνω από τη νομιμοφροσύνη τους προς το κράτος. Όμως, οι Χριστιανοδημοκράτες ήταν επίσης πλουραλιστές: Ήταν ικανοποιημένοι με μια ομοσπονδιακή, νομικά κατακερματισμένη ευρωπαϊκή κοινότητα που έμοιαζε με μια μεσαιωνική αυτοκρατορία περισσότερο από ό, τι ένα σύγχρονο κυρίαρχο κράτος.

Καταστροφείς Κομμάτων

Μετά από δεκαετίες ως κυρίαρχη πολιτική δύναμη στην Ευρώπη, οι χριστιανοδημοκράτες τώρα αντιμετωπίζουν την προοπτική τής παρακμής. Ορισμένοι παρατηρητές έχουν κατηγορήσει την εκκοσμίκευση για την αποδυνάμωση της λαϊκής υποστήριξης. Είναι αλήθεια ότι, από τις αρχές τής δεκαετίας τού 1960, οι εκκλησίες αδειάζουν σε όλη την ήπειρο. Αλλά τα ίδια τα κόμματα είχαν ήδη αρχίσει να επιμένουν ότι κάποιος έπρεπε απλά να υιοθετήσει τις ανθρωπιστικές ιδέες προκειμένου να είναι ένας καλός χριστιανοδημοκράτης. Το πραγματικό πρόβλημα προέκυψε με τον θρίαμβο ακριβώς του πολιτικού μοντέλου που είχαν ξεκινήσει να προωθούν από το 1950.

Οι περισσότερες χώρες τής Κεντρικής και Ανατολικής Ευρώπης υιοθέτησαν αυτό το μοντέλο μετά το 1989, αλλά σχεδόν καμία από αυτές δεν ανέπτυξε χριστιανοδημοκρατικά κόμματα στο καλούπι τής γερμανικής Χριστιανοδημοκρατικής Ένωσης ή της ιταλικής Χριστιανικής Δημοκρατίας. Σε ορισμένες χώρες, όπως η Καθολική Πολωνία, οι χριστιανοδημοκρατικές ομάδες φαίνονταν περιττές∙ Σε άλλες, αποδείχθηκε ότι ήταν ριζικά διαφορετικές από τις δυτικοευρωπαϊκές αντίστοιχές τους σε δύο σημεία: Ήταν έντονα εθνικιστικές, και ως εκ τούτου δεν επιθυμούσαν να παραχωρήσουν ένα μεγάλο μέρος τής εθνικής κυριαρχίας που ανέκτησαν από την Σοβιετική Ένωση∙ Και ήταν πολύ πιο λαϊκιστικές, μη βλέποντας λόγο να μην εμπιστεύονται τον απλό λαό που είχε καταφέρει να επιβιώσει από τα κράτη των σοσιαλιστικών δικτατοριών, με το ήθος του φαινομενικά άθικτο.

Εν τω μεταξύ, πιο δυτικά, οι χριστιανοδημοκράτες έχασαν τον μεγαλύτερο εχθρό τους – τον κομμουνισμό - και μαζί με αυτόν πολύ από τον ιδεολογικό συνεκτικό ιστό που κρατούσε ενωμένους τους συχνά εριστικούς πολιτικούς συνασπισμούς. Στην Ιταλία, οι χριστιανοδημοκράτες είχαν συμμετάσχει σε κάθε κυβέρνηση από την εποχή τού Β’ Παγκοσμίου Πολέμου - με το αιτιολογικό ότι το Κομμουνιστικό Κόμμα, το μεγαλύτερο στην Δυτική Ευρώπη, έπρεπε να μείνει απ’ έξω. Στις αρχές τού 1990, η εξαιρετικά διεφθαρμένη Democrazia Cristiana κατέρρευσε. Στην συνέχεια, ο Ιταλός πρωθυπουργός Σίλβιο Μπερλουσκόνι - ένας άνθρωπος όχι γνωστός για την αυστηρή τήρηση της καθολικής ηθικής - στην πραγματικότητα κληρονόμησε τις ψήφους τού κόμματος.

Σίγουρα, η Χριστιανική δημοκρατία, όπως αποδεικνύεται από την πρόσφατη επιτυχία τού ΕΛΚ, παραμένει η ισχυρότερη πολιτική δύναμη της ηπείρου στα χαρτιά. Ωστόσο, το κόμμα είναι βαθιά δυσλειτουργικό. Οι διαφωνίες για τον κορυφαίο υποψήφιό του για την προεδρία τής Ευρωπαϊκής Επιτροπής, τον Jean-Claude Juncker, καταδεικνύει το ζήτημα. Κατά την διάρκεια της προεκλογική εκστρατείας, κάποιοι ηγέτες τού ΕΛΚ προσπάθησαν να επωφεληθούν από τα αισθήματα κατά της ΕΕ. Ο Μπερλουσκόνι προσπάθησε επίσης να ηγηθεί της αντι-γερμανικής δυσαρέσκειας και απευθύνθηκε στους Ιταλούς που έχουν απηυδήσει με την λιτότητα. Αμέσως μετά τις εκλογές, ο Viktor Orbán, ο Ούγγρος πρωθυπουργός και πρώην αντιπρόεδρος του Ευρωπαϊκού Λαϊκού Κόμματος, επιτέθηκε στον Juncker ως ότι είναι ένας παρωχημένος υποκινητής τής ευρωπαϊκής ενότητας, μιας ενότητας που δεν σέβεται τα εθνικά κράτη και τις παραδόσεις τους. Τα τελευταία χρόνια, ο Orbán είχε ήδη προκαλέσει εντύπωση όταν κήρυξε «πόλεμο ανεξαρτησίας» - σκοπός τού οποίου ήταν να κάνει τους Ούγγρους ανεξάρτητους από ακριβώς το πολιτικό πρόγραμμα τού ΕΛΚ, την ευρωπαϊκή ολοκλήρωση.

---------------------------------------------------------------

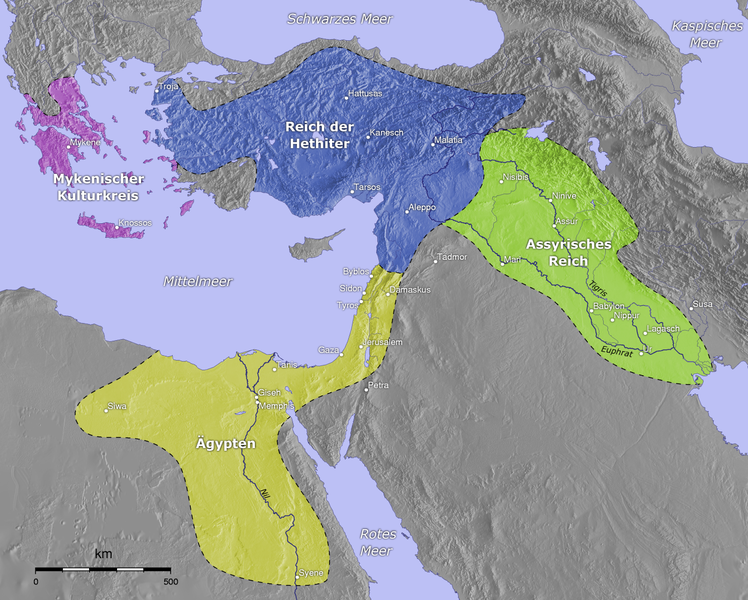

Όταν ο Λιθουανός, ο Ούγγρος ή ο Βούλγαρος λένε «Ευρώπαική Ένωση» και «δημοκρατία» εννοούν λεφτά, ενώ όταν λένε «ΝΑΤΟ» εννοούν ότι θέλουν να λυθούν τα εθνικά προβλήματα του παρελθόντος που τους βαρύνουν. Εννοούν την Συνθήκη του Τριανόν και του Νεϊγύ. Και των πολλών άλλων ανάλογων που υπάρχουν στην... «θύρα της Ευρώπης». Όταν ο Ούγγρος λέει «Ευρωπ. Ένωση» και «ΝΑΤΟ», δεν εννοεί ότι του λείπουν δημοδιδάσκαλοι που διδάσκουν την δημοκρατία'εννοεί ότι θέλει αλλαγή των συνθηκών εκείνων που τον μετέβαλαν από ένα προεξέχοντα λαό της κεντρικής Ευρώπης, σε μια μειονότητα γύφτων. Και όταν λέει τα ίδια πράγματα ο Αλβανός, εννοεί ότι θέλει μια λύση εκείνων των προβλημάτων που μετέβαλαν την χώρα του -μια από τις πλουσιότερες και στρατηγικότερες χώρες της Μεσογείου, που αποτέλεσε τον φορέα ενός από τα πιο ανεπτυγμένα και πλούσια τμήματα της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας ως τις αρχές του 19ου αιώνα- σε μια επικράτεια από παρίες.

Έχει όμως η «Ευρώπη» καμία λύση γι'αυτά τα προβλήματα;. Τους «διανοούμενους της Ευρώπης» είδαμε ότι δεν τους απασχολούν τέτοια προβλήματα, ενώ με την κρίση της Βοσνίας είδαμε ότι η «ευρωπαϊκή πολιτική» εξαντλείται απλώς στο «Prestige» των «μεγάλων δυνάμεων» του παρελθόντος. Ακόμη... Αλλά λύσεις δεν είδαμε, ακριβώς διότι μέσα στα πλαίσια της παραδεδομένης πολιτικής δεν υπάρχουν λύσεις γι'αυτά τα προβλήματα. Τι λύση μπορεί να είναι τα «καντόνια»; Η Βοσνία είναι φυλετικά σερβική (και οι μωαμεθανοί, Σέρβοι φυλετικά είναι) με μεγάλους θύλακες μωαμεθανών στο κέντρο και ορισμένους Κροατών νοτιοδυτικά. Πως θα δεχθεί τα καντόνια ο Σέρβος; Να γίνει πάλι η Βοσνία δύο κράτη; Ο χωρισμός θα περάσει αναγκαστικά μέσα από τους μωαμεθανούς, οπότε δεν μπορούν να το δεχθούν αυτοί.

Αυτές οι «λύσεις», στις οποίες εξαντλήθηκαν οι προσπάθειες των «μεσολαβητών», δεν αποτελούν λύσεις, διότι ακριβώς προέρχονται από δυτικοευρωπαϊκές παραστάσεις περί πολιτικής του παρελθόντος...

---------------------------------------------------------------

Μέρος τού προβλήματος, λένε ορισμένοι παρατηρητές, είναι ότι το ΕΛΚ - περιλαμβάνοντας όχι λιγότερες από 73 κόμματα-μέλη από 39 χώρες - είναι απλά υπερεκτεταμένο. Στις αρχές τής δεκαετίας τού 1990, ο Helmut Kohl, τότε καγκελάριος τής Γερμανίας, και ο Wilfried Martens, πρώην πρωθυπουργός τού Βελγίου και στην συνέχεια πρόεδρος τού ΕΛΚ, στρατολόγησαν πολιτικούς σε όλη την Ευρώπη, κράτησαν σχετικά χαμηλά στάνταρ, με ελάχιστο ενδιαφέρον για την πραγματική δέσμευση των νέων οπαδών στα ιδανικά τού κόμματος. Ο Κολ ήταν ανένδοτος ότι οι χριστιανοδημοκράτες δεν είχαν χτίσει την Ευρώπη απλώς για να την παραδώσουν στους σοσιαλιστές, και ότι το ΕΛΚ έπρεπε να παραμείνει η μεγαλύτερη πολιτική ομάδα τής ηπείρου με κάθε κόστος.

Το βαθύτερο πρόβλημα, όμως, αφορά στην ιδεολογική ιδιαιτερότητα του κινήματος. Ηγέτες όπως ο Κολ ήταν πρόθυμοι να αναλάβουν κινδύνους για την Ευρώπη. Σήμερα, δύσκολα κάποιος μπορεί να βρει αληθινούς πιστούς που θα βάλουν την σταδιοδρομία τους σε κίνδυνο για την ευρωπαϊκή ολοκλήρωση, και λιγότερο από όλους η σημερινή καγκελάριος της Γερμανίας. Στα ερωτήματα σχετικά με τις αγορές και την ηθική, οι χριστιανοδημοκράτες είχαν μια πρώτης τάξεως ευκαιρία να επανεφεύρουν τον εαυτό τους μετά την οικονομική κρίση: Θα μπορούσαν να έχουν φέρει πίσω τα παλιά ιδανικά τους για μια οικονομία, για παράδειγμα, στην οποία η ηθική μονάδα είναι μια κοινωνική ομάδα με νομιμοποιημένα συμφέροντα, όχι ένα άτομο που μεγιστοποιεί τα κέρδη του. Αντ’ αυτού, οι Γιούνκερ και Μέρκελ έχουν αγκαλιάσει πλήρως τις συμβατικές πολιτικές λιτότητας, και σε μεγάλο βαθμό έχει ξεχαστεί ότι ο Ιταλός πρωθυπουργός Matteo Renzi - η μεγάλη ελπίδα τής ευρωπαϊκής Αριστεράς - στην πραγματικότητα ξεκίνησε ως μέλος τού ανασυσταθέντος Popolari (και, ακόμα νωρίτερα, ως καθολικός πρόσκοπος).

Οι χριστιανοδημοκράτες τής Ευρώπης θα μπορούσαν επίσης να αντιγράψουν μια σελίδα από το πρόγραμμα των Αμερικανών συντηρητικών, επικεντρωνόμενοι ξανά στα κοινωνικά ζητήματα και διεξάγοντας έναν δικό τους Kulturkampf εναντίον τής εκκοσμίκευσης. Μερικοί έχουν ήδη δοκιμάσει: Κατά την διάρκεια της τελευταίας δεκαετίας, το ισπανικό Λαϊκό Κόμμα κινητοποίησε τις Καθολικές ψήφους ενάντια στον σοσιαλιστή πρωθυπουργό José Luis Zapatero, ο οποίος είχε προτείνει την νομιμοποίηση των γάμων μεταξύ ομοφύλων. Σε αντίθεση με τα κλισέ τής θρησκευόμενης Αμερικής και της άθρησκης Ευρώπης, εξακολουθεί να υπάρχει σημαντικό δυναμικό για τέτοιου είδους εκστρατείες σε ορισμένες χώρες τής Νότιας και της Ανατολικής Ευρώπης. Είναι χαρακτηριστικό, πάντως, ότι οι Ισπανοί ψηφοφόροι τελικά απομακρύνθηκαν από τον Θαπατέρο για τους χειρισμούς του στην ευρωπαϊκή κρίση.

Διαγωνισμός Δημοφιλίας

Οι χριστιανοδημοκράτες αντιμετωπίζουν ένα δύσκολο δίλημμα. Οι πολιτικοί τους στόχοι είναι απλώς οριακά διαφορετικοί από εκείνους των σοσιαλδημοκρατικών κομμάτων στα οικονομικά ζητήματα. Ένας Kulturkampf είναι επικίνδυνος, αλλά το να είναι κανείς πολύ μέσα στην επικρατούσα τάση στα κοινωνικά θέματα, δημιουργεί πολιτικό χώρο για τις ομάδες που παρουσιάζονται ως πραγματικά συντηρητικές. Τα πολιτικά κόμματα, όπως το «Εναλλακτική για την Γερμανία», το οποίο επικεντρώνεται κυρίως στο να αντιτίθεται στην ΕΕ αλλά υπερασπίζεται όλο και περισσότερο την παραδοσιακή ηθική, και το γαλλικό Εθνικό Μέτωπο, είναι οι ευεργετηθέντες.

Το πιο σημαντικό, οι χριστιανοδημοκράτες βρίσκονται κάτω από έντονη πίεση από τους δεξιούς εθνικιστές και τους λαϊκιστές. Και δεδομένου ότι δεν τολμούν πλέον να υπερασπιστούν τα φιλόδοξα σχέδια για την ευρωπαϊκή ολοκλήρωση, οι πάλαι ποτέ αρχιτέκτονες της ηπειρωτικής ενότητας είναι περισσότερο ή λιγότερο ανυπεράσπιστοι. Οι πολιτικές τους υπέρ των διευθετήσεων δεν λειτουργούν ως απάντηση στους λαϊκιστές, που ευδοκιμούν στην πόλωση και στις πολιτικές σχετικά με τις ταυτότητες. Η παλιά τάξη των συνασπισμών που στήριξε την ευρωπαϊκή ολοκλήρωση στις κάλπες και επωφελήθηκε από αυτήν οικονομικά - η μεσαία τάξη και οι αγρότες - έχει μειωθεί σχεδόν παντού. Αυτός ο μακροπρόθεσμος μετασχηματισμός καθιστά απίθανο ότι η χριστιανοδημοκρατία θα ανακτήσει ποτέ την δεσπόζουσα θέση που είχε στα μεταπολεμικά χρόνια. Αυτό αφήνει την

ΕΕως ένα κούφιο κέλυφος: Τα ιδανικά που κάποτε κινητοποιούσαν τα σχέδια της ολοκλήρωσης φαινομενικά έχουν ξεχαστεί, υπερασπιζόμενα μόνο από μικρά κόμματα όπως οι Πράσινοι.

Η

Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωσηδεν θα καταρρεύσει ως αποτέλεσμα όλων αυτών. Το πραγματικό πρόβλημα είναι η μισοτελειωμένη ευρωζώνη. Όπως οι Ευρωπαίοι έχουν μάθει με μεγάλο κόστος κατά τα τελευταία χρόνια, η ευρωζώνη όπως υπάρχει σήμερα είναι ελλιπής και μη συνεκτική: Είναι μια νομισματική ένωση που δεν επιτρέπει τον σωστό συντονισμό των δημοσιονομικών πολιτικών ή μια πραγματική σύγκλιση των οικονομιών των συμμετεχόντων. Μια πλημμύρα φθηνού χρήματος από την Ευρωπαϊκή Κεντρική Τράπεζα - η τρέχουσα λύση για την κρίση τού ευρώ - απέτυχε να αντιμετωπίσει τα διαρθρωτικά προβλήματα των μεμονωμένων κρατών και της ευρωζώνης στο σύνολό της. Το να λειτουργήσει το ευρώ μακροπρόθεσμα θα απαιτήσει μια προθυμία να αναληφθούν πολιτικοί κίνδυνοι και υλικές θυσίες. Και οι ημέρες που ο χριστιανοδημοκρατικός ιδεαλισμός ήταν ικανός να παράγει και τα δύο, έχει τελειώσει.

Jan-Werner Müller

Copyright © 2002-2012 by the Council on Foreign Relations, Inc.

All rights reserved.

---------------------------------------------------------------

Για περαιτέρω ιχνηλάτηση και πληρέστερη προοπτική

---------------------------------------------------------------

.~`~.

ΙΙ

How Obama Is Driving Russia and China Together

American bluff and bombast toward Moscow has stoked Russian nationalism, convinced Putin we're weak, and fostered a dangerous realignment.

*

PRESIDENT BARACK Obama likes to say that America and the world have progressed beyond the unpleasantness of the nineteenth century and, for that matter, much of the rest of human history. He could not be more wrong. And as a result, he is well on the way to repeating some of history’s most dangerous mistakes.

Few would think to compare Obama to Russia’s last czar, Nicholas II. Nevertheless, Emperor Nicholas II, like President Obama, thought of himself as a man of peace. A dedicated arms controller, he often called for a rules-based international order and insisted that Russia wanted peace to focus on its domestic priorities. Of course, Obama’s philosophy of governance and world outlook differ profoundly from those of this long-dead autocrat. Yet there is one disturbing assumption they appear to share in foreign affairs: the idea that as long as you do not want a war, you can pursue daring policies without risking conflict or even war.

Consider Ukraine. In March, Obama said, “We are not going to be getting into a military excursion in Ukraine.” Nicholas II also declared that there would be no war between Russia and Japan on multiple occasions on the eve of their 1904–1905 conflict. How could there be a war if he did not want it, the czar said to his advisers, especially because he considered Japan far too small and weak to challenge the Russian Empire.

While Nicholas II genuinely did not want war, he assumed that Russia could get away with almost whatever it wanted to do in the Far East. At first, Japan reluctantly acquiesced to Russian advances—but Tokyo soon began to warn of serious consequences. Overruling his wise advisers, Finance Minister Sergei Witte and Foreign Minister Vladimir Lamsdorf, the czar decided to stay the course. He saw Japan’s concessions as evidence that the “Macacas,” as he derisively called the Japanese, would not dare to challenge a great European power. When they did, the result was humiliation and a devastating blow to Russia’s global standing.

From the outside, the Obama administration appears to be following a similar trajectory in its approach to Russia. Top officials seem to believe that short of using force, the United States can respond as it pleases to Moscow’s conduct in Ukraine without any real risks. At the same time, the administration has gone to great lengths to personalize the dispute by targeting Russian president Vladimir Putin’s associates and graphically describing Putin’s flaws and transgressions, including in State Department fact sheets. And even as it takes these measures, liberal hawks and neoconservatives are denouncing Obama as weak for not going further.

The weakness is there, but the bellicose stances that Obama’s critics espouse are unlikely to deter Moscow and might even do the opposite. So far, the United States has fundamentally miscalculated in dealing with Russia. By indulging in bluff and bombast, it has created the worst of all worlds. It has stoked Russian militant nationalism, convinced Putin that the United States is weak and indecisive, and exposed the divisions within the West. These difficulties will only be compounded if the Obama administration yields fully to the incessant scoldings of those in Washington who are eager to start Cold War II, regardless of whether they are really prepared to fight it.

Especially misleading is the sense that the Kremlin’s apparent steps back from the brink in late May are due to the success of U.S. policy. The easiest invasion to prevent is one that was never really intended; much evidence indicates that Putin well understood the great costs of a large-scale intervention in Ukraine and likely sought leverage rather than control, much less possession. But if U.S. policy makers and politicians decide that Washington and Brussels can return to business as usual by encouraging newly elected Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko to bring his country into NATO, dismiss Moscow’s concerns, and crush opposition in eastern and southern Ukraine, Putin’s resolve could grow, as it did in the case of Crimea.

Moreover, efforts to isolate and punish Moscow will push it into seeking closer ties with China. Supplying Ukraine or the Baltics with a blank check would only encourage the kind of behavior that may cost them dearly if Russia disregards NATO’s red lines. The appropriate response to Russia is to consider how we can convince it to choose restraint and, when possible, cooperation. Such an approach must be based on an analytical assessment of how Russia defines its interests and objectives rather than the way American policy makers would define them in Moscow’s shoes. It will also require a combination of credible displays of force that appear distasteful to Obama and credible diplomacy that looks distasteful to his critics.

In the Ukraine crisis, Obama should have kept all options open rather than publicly renouncing a military response or even meaningful military aid. And that possibility would have had to be communicated to Putin quietly but clearly, including through significant troop movements, as Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger did during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. America’s obligation to protect its allies includes a responsibility to avoid exposing them to unnecessary danger with actions that may tempt Russian leaders to demonstrate their toughness without deterring them in any real sense—a posture that could force the United States and NATO to choose between war and humiliation. An arrangement that can bring lasting results would require tact and diplomacy, vision and strength—all qualities that have been conspicuously lacking in the Obama administration.

Obama’s impulse to personalize the dispute suggests that he has been personally offended by Putin. No doubt Russia’s president has a unique background and macho style that make it easy to portray him as the devil incarnate, particularly in Western media outlets that prize simple narratives over complex storytelling or analysis. What’s more, his political practices inside Russia are increasingly authoritarian and contemptuous of dissent. Though Putin publicly emphasizes the rule of law and campaigns against corruption, those close to him operate with virtual impunity, which encourages lower-level bureaucrats to ignore the Kremlin’s demands to stop corrupt behavior. Perhaps ironically, Putin’s general success in taming the oligarchs’ political ambitions has in practice further empowered the bureaucracy at the expense of civil society; the oligarchic media empires of the 1990s were far from objective, but did serve as a check on officials at all levels. The State Duma is dominated by the ruling United Russia party and all factions defer to the president on key issues.

Internationally, the Russian government frequently pressures its neighbors to play by Moscow’s rules and does not hesitate to use energy exports as a political weapon. In Ukraine, Putin retracted his own misleading initial denials of a major Russian military role in Crimea. The Kremlin’s demands that Kiev’s interim government avoid using force against armed rebels because no country should employ the military against its own people rang hollow after Russia’s support for Bashar al-Assad’s brutal rule in Syria—not to mention Moscow’s own wars in Chechnya. Of course, the Obama administration, too, does not suffer from excessive consistency, first demanding that Ukraine’s Viktor Yanukovych refrain from using force against protesters and then voicing support as the new Kiev government did exactly that.

But whatever one makes of Putin’s KGB background and his leadership style, it takes two to tango. And thus it is impossible to set aside Obama’s own origins as a civil-rights activist and community organizer whose passion animates an ends-justify-the-means attitude toward bending and exploiting the rules both domestically and internationally, as seen in the recent agreement for the release of Taliban captive Bowe Bergdahl. Unlike Ronald Reagan—another moralist president—Obama does not appear truly occupied with international affairs, which seem like an unwelcome distraction from his transformative domestic agenda. He is thus disengaged and uninterested in understanding the other side. When combined with three other contrasts with the Reagan administration—a weak foreign-policy team, defense cuts and reluctance to use force—this produces a pushy but casual and weak moralism. Obama appears to dismiss Chinese and Russian interests because their undemocratic governments by definition make their interests less legitimate, while he simultaneously looks reluctant to do what is necessary to implement his numerous red lines. As a result, rivals like Russia and China are more offended than deterred. At the same time, allies and friends question Obama’s resolve after decisions like the administration’s announced withdrawal from Afghanistan no matter what happens there.

UNDERSTANDING THE Ukrainian crisis requires going beyond what is happening in that bitterly divided country to assess the complex politics of the post-Soviet region and the conflicting impulses on both sides. What worries the United States, the European Union, and their allies and friends is the question of, as the Economist put it, in its typically eloquent but superficial way, “Where is Globocop?” How will America’s inability to impose its will on a defiant Russia affect the West’s credibility in upholding the world order? During the Cold War, the United States was expected and able to protect NATO members and other key allies such as Japan, Israel and Saudi Arabia. Still, the realities of the rival Soviet bloc created objective constraints on how far Washington policy makers were prepared to go and enforced intellectual discipline in their decision making. During the post–Cold War years, the United States and its allies gradually concluded that they could act as masters of the world without meaningful opposition from another great power. They reached this view by trial and error, starting with the fully justified and remarkably easy Gulf War and continuing with (for America and NATO) bloodless victories in the Balkans and later setbacks in Iraq and Afghanistan. Since no other great power sought crises in the latter two countries, neither of these disappointments became an outright defeat like what transpired in Vietnam—though they have fueled a new reluctance to use military power among President Obama and many Americans across the political spectrum.

America’s professional military force—and NATO allies’ willingness to stand tall behind a U.S. shield without spending much on their own capabilities—facilitated this new conventional wisdom. Washington and Brussels forged themselves into a new “international community” that felt entitled and able to act on behalf of all humanity without special effort to assess humanity’s preferences in advance or reactions afterward. The expansion of NATO and the European Union to include especially pro-American and anti-Russian new members from the former Soviet bloc contributed to a spirit of transatlantic solidarity and missionary zeal unprecedented since the immediate post–World War II period. But unlike the transatlanticism of the 1940s and 1950s, this version came with a sense of entitlement and impunity founded on the unexpectedly easy victory by forfeit in the Cold War and the apparent absence of a serious geopolitical rival.

In reality, of course, precisely as this mind-set took firm hold among American and European elites, the world was changing. For much of this period, Beijing was generally willing to acquiesce to U.S. and European international conduct. Over time, however, China began to establish itself as an emerging great power and to act accordingly. Chinese leaders share many of their Russian counterparts’ reservations about assertive Western global hegemony and democracy promotion, and they have become increasingly comfortable acting on them—including in concert with Moscow, as was most clear in the UN Security Council deliberations over Syria.

At the same time, Russia recovered from its post-Soviet collapse and the disastrous, radical economic reforms of the 1990s to become a resurgent power. While Russia is still primarily a regional power, its size and geography make that region a very substantial one. Moreover, the asymmetries between Russia and most of its neighbors make it a power they ignore at their peril. Finally, Russia’s modernized strategic nuclear forces gave Putin and his colleagues the sense that no one would dare to treat Russia like Yugoslavia or Iraq.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its threat to the rest of Ukraine thus challenged two decades of experience. Moscow’s new assertiveness triggered memories of the Cold War and prompted righteous indignation in the United States and Europe, where many reacted angrily to the idea that a former KGB officer and his lieutenants could threaten their self-evidently virtuous liberal world order. Moscow had a different perspective, of course, born of escalating resentment of the way in which the West defined and enforced the rules, perhaps most notably in NATO’s interventions in Bosnia and Kosovo and the West’s support for Kosovo’s independence. Notwithstanding Polish foreign minister Radoslaw Sikorski’s statement that Russia’s annexation of Crimea was the first time since World War II that someone “has taken a province by force from another European country,” the first occasion was actually NATO’s removal of Kosovo from then-democratic Serbia, despite a UN Security Council resolution and eight years as a NATO protectorate that removed any humanitarian threat to the Kosovars. Because of events like this, Kremlin officials increasingly saw U.S. and European proclamations about international law through the lens of the enduring Russian proverb that rules are for servants, not masters. At the same time, they were angered that after assurances that NATO enlargement would make Russia more secure, the alliance’s new members seemed to make NATO only more hostile toward Russia. After several years of rapid economic growth and increases in military spending, Moscow saw itself as a master capable of enforcing its will—at least along its own frontiers.

Meanwhile, focused on domestic politics and entranced by post–Cold War triumphalism, America’s political elites worked assertively to short-circuit debate and to marginalize anyone who questioned their international assumptions. The end result was a foreign policy in which, as George F. Kennan described it, “a given statement or action will be rated as a triumph in Washington if it is applauded at home in those particular domestic circles at which it is aimed, even if it is quite ineffective or even self-defeating in its external effects.” Publics in America—and Europe—were also proud of their international successes and were thus prepared to accept their governments’ activism so long as it worked and so long as continued prosperity made it cheap. Now, however, they are much less willing to support interventionist policies, meaning that out-of-touch elites will likely lack the political support to finish what they might succeed in starting.

WHAT THE triumphalists failed, and continue to fail, to recognize is how little is truly new in world politics. This is not the first time that a dominant alliance has claimed exceptional virtue and exceptional prerogatives. Quite the contrary. During the early nineteenth century, for example, the Holy Alliance made some of the same arguments in outlining its obligations to protect the kings and princes of Europe. Claiming divine virtue and superior political systems, its proponents acted with no less moral conviction or entitlement than today’s Western democracy promoters.

Of course, the combination of human nature and democratic politics virtually assures that while promoting universal values, powerful nations and alliances also take care of their interests—and see their opponents’ interests and perspectives as inherently inferior. In fact, in proclaiming a unipolar world and making himself a global democracy enforcer, former president George W. Bush briefly went even further than Russia’s Czar Nicholas I, who won fame as the “gendarme of Europe” for making the Continent safe for autocracy.

Statesmen like Otto von Bismarck and Benjamin Disraeli ruthlessly advanced what they saw as their nations’ true interests while coldly appraising their rivals’ aims and views. As the German author Emil Ludwig wrote, what most repelled the Iron Chancellor in dealing with Russia was “that country’s bold claim to equality of right—a claim he has never been able to endure, whether in politics, family life, or ministerial councils.” Despite this, Bismarck understood that Russia was a major factor in European politics and one that Prussia’s kings had to live with—and could even find useful to advance their core interests, including in unifying Germany. Today’s Western leaders, however, are more preoccupied with short-term political fortunes than strategic national interests.

Nowhere is this clearer than in America’s relations with Russia. The swing from euphoria over the fall of the Berlin Wall to noisy calls for a new cold war provides a sobering reminder of the superficiality of American analysis of Russia’s motives and goals. Instead of responding emotionally to Russian actions, the United States should adopt a more calculating approach toward Moscow. One fundamental mistake that those thirsting for a cold war are making is to assume that Putin has a grand master plan for re-creating the Soviet empire. Putin’s long-term desire to enhance Russia’s power and influence is clear—and he has not hesitated to act on it in the current crisis over Ukraine. Yet, he has also sought partnership with the West at times and clearly hopes—correctly or incorrectly— that Russia’s annexation of Crimea does not foreclose future engagement.

Indeed, looked at from a historical perspective, Moscow’s conduct does not suggest a crusade to rebuild the Soviet Union. Yes, Putin has said that he considers the collapse of the USSR to be a terrible tragedy, and he clearly seeks a greater political, security and economic role for his country in the post-Soviet region. But consider this: until the crisis in Ukraine, Moscow used force against a neighboring state only one time, in 2008, after Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili first ordered attacks on Russian peacekeepers in South Ossetia. Before that, Abkhazia and South Ossetia had been largely under de facto Russian control for years. Despite the fact that both are contiguous to Russia’s territory and reliant on Russian subsidies to survive economically, the Kremlin did not choose to integrate them into Russia.

Then there is Ukraine. Russia’s annexation of Crimea was not predetermined and resulted from a complex and multidimensional process. There is no evidence that Putin would have tried to take over Crimea without the combination of humiliating defeat and political opportunity that Obama and his EU associates presented to him after their Ukrainian political protégés drove former president Viktor Yanukovych from office without quite following the parliamentary procedures required to impeach him under the country’s constitution. The result was regime change, which is not a rules-based policy, especially when it assertively extends the West’s—let’s be honest about it—sphere of influence to the single most strategically, economically, historically and emotionally significant area on Russia’s borders. After contributing to the Crimean fiasco, it is little wonder the president sounds so defensive.

IF THE United States and the European Union want to prevent Putin from taking further action, they must be clear-eyed about the policies that can produce results at an acceptable cost. Targeted sanctions against Putin’s inner circle and other Russian officials and politicians—some of whom appear to have been sanctioned for reasons unrelated to Ukraine—will not change Russian policy. Their impact is too limited, and, unlike their counterparts in Ukraine, Russian tycoons do not have political influence or control members of the legislature. Moreover, Putin can compensate them for any losses even as his security apparatus watches them for signs of weakness under foreign pressure.

Further U.S. and EU sanctions could have a severe impact on Russia’s economy. However, Americans should understand that both Kremlin officials and Russia’s citizens would see crippling “sectoral” sanctions against Russia’s financial institutions or energy companies as acts of economic warfare. Such sanctions would not only impose costs on our own side—particularly the Europeans, and Germany most of all—but also encourage the Russian government to treat the United States and its allies as enemies rather than superiors. History provides scant evidence to suggest that Moscow would change course; far-reaching sanctions have not changed policy in Cuba, North Korea or Iran. Likewise, the U.S. oil embargo targeted against Japan before World War II did not contain the crisis—it accelerated it. Putin is supported by a political consensus that submission is no longer a sustainable foreign-policy option.

Moreover, when one hears U.S. officials and members of Congress declare that sanctions have brought Iran to its knees, it is hard to know whether to laugh or cry. Iran has not abandoned enrichment, stopped developing long-range missiles or ceased assistance to Syrian president Bashar al-Assad. Russia is economically much stronger than previous sanctions targets such as Iran, and as of this writing, some 86 percent of the population supports Putin, at least for now, and many on the Internet claim that if anything, Putin is the accommodationist.

Launching economic war against Russia would mean entering uncharted territory. Moscow would have no shortage of options, and many are already under discussion publicly and privately. First, Russia might start cooperating with anti-Western movements from Afghanistan to the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. The list of such governments and groups interested in Russian assistance would be long and imposing. According to Mikhail Gorbachev’s adviser Alexander Yakovlev, when the U.S.-Soviet relationship reached a crisis level in 1983–1984, former Soviet leader Yuri Andropov ordered considerable expansion of the USSR’s support for terrorism, something that contributed to the dramatic hostage takings in Lebanon.

Among plausible recipients of Russia’s sophisticated weapons might be Iran, which is currently suing Russia for failing to fulfill its obligation to supply S-300 antiaircraft missiles. Russia suspended delivery of these weapons at the urging of the Israeli government, which it considers friendly. If it chose, however, Moscow could bypass the more moderate government of Hassan Rouhani and offer expedited delivery of the S-300 systems, or the more advanced S-400, directly to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. Israel might want to attack Iran’s nuclear installations before the missiles arrived—something that could trigger a war in the Gulf, attacks on American targets, oil and gas supply disruptions, and huge increases in energy prices. Russian officials may expect that this would improve the Kremlin’s bargaining position vis-à-vis the West, especially Europe. Avoiding concessions to Moscow might mean making them to Tehran, possibly at Israel’s expense. Which is less palatable?

The Obama administration should also be much more careful about its message to Ukraine’s government. Visible U.S. support is important, but Washington must avoid providing officials in Kiev with the same false sense of support that facilitated Saakashvili’s ruinous confrontation with Moscow.

An escalating dispute in Ukraine could not but affect already-struggling European economies. Investor confidence could become especially shaky in the Baltic states, where Moscow could exploit any economic slowdown to mobilize significant and poorly integrated ethnic Russian communities in Estonia and Latvia to destabilize governments. Latvia’s capital, Riga, already has an ethnic Russian elected mayor who openly favors a closer relationship with Moscow.

Some will argue that Moscow would not risk this with NATO members. But notwithstanding President Obama’s references to Russia’s weakness, Russia has an impressive superiority in conventional forces vis-à-vis Ukraine and in Central Europe and a roughly ten-to-one superiority in tactical nuclear weapons, of which it has an estimated two thousand, compared to about two hundred deployed in Europe for the United States. Russian military planners consider tactical nuclear weapons an important component in the overall balance of forces and are preparing integrated war plans that include nuclear options. Even more dangerous, Russian generals might assume that NATO would recognize this imbalance and would therefore not dare to escalate.

Finally, while Russia may have limited options to impose direct economic harm on the United States, Americans should recognize that attempting to use U.S. dominance in the international financial system as an instrument against another major power will encourage not only Moscow but also other nations to see the American-centered global financial system as a threat. This could put new momentum behind existing efforts to weaken America’s international financial role and might even prompt some to seek to undermine the global financial system as we know it today. Since that system is a key source of U.S. strength and prosperity, Obama administration officials should think twice before weaponizing international finance. New reports suggest that Russian companies are already exploring nondollar settlements with Chinese firms; even if modest, this could open a Pandora’s box.

THESE OMINOUS possibilities are far from inevitable. Putin and his associates would have to consider huge potential costs to Russia—and to their personal fates—before upping the ante with NATO. Nevertheless, these dire scenarios are not fantasy. What is remarkable is that few in the U.S. executive branch or Congress are paying the slightest attention.

It is not merely intellectually inconsistent but also peculiar that the same officials and commentators who view Putin as an evil genius also expect him to accept Western punishment with a combination of easily dismissed bluster and toothless symmetrical action. Likewise, it may be politically convenient to ignore the very real possibility of Russia drawing closer to China, but it is strategically reckless. By any logical criteria, American leaders should see China rather than Russia as their greatest challenge.

China is both more central to the world economy and more integrated into the world economy than Russia. Despite its assertive conduct, Beijing is not seeking conflict with the United States. Like Russia’s leaders, however, Chinese officials see Washington as bent on containment and a potentially dangerous democracy-promotion policy. This is an important confluence of interests between China and Russia that U.S. leaders must consider. The post–Cold War world is over and a new world is emerging.

Of course, there are big differences in interests between Russia and China—and each has enduring grievances against the other. No less important, China’s nominal GDP is roughly four times the size of Russia’s, and it is much more connected to the U.S. economy. Thus, under normal circumstances, Beijing and Moscow feel that they need Washington, particularly when it acts in concert with Brussels, more than they need each other. But are today’s circumstances still normal? If both governments believe they face dangerous pressure, each may see the other as a natural partner in balancing against the West. New public U.S. cyberespionage charges against Beijing may further sway China toward Moscow.

While China abstained from voting on the resolutions concerning Crimea in the UN Security Council and the UN General Assembly, it was still pretty clear where Beijing’s sympathies rested. China is reluctant to support Russian positions openly, especially in view of its own separatism concerns. Despite this, China does not approve at all of the way the United States and the European Union have handled the Ukraine situation. The Ukraine crisis will push Russia and China closer, but exactly how much closer depends on U.S. and EU policies. At a minimum, they have much that unites them, including difficulties with their immediate neighbors, each of which are supported by the United States. Putin and Chinese president Xi Jinping signed a major natural-gas agreement as well as an unreported foreign-policy coordination agreement during their May 2014 meeting; though neither may live up to Moscow’s hopes, U.S. and European officials will take grave risks if they ignore or minimize the Sino-Russian relationship. From time immemorial, efforts to isolate a major power without defeating it have generally led to international realignments and new alliances—and whatever Obama may think, the present century is unlikely to differ from the previous five millennia of recorded history. A contest between two revisionist coalitions—the hegemonic West and a rising China–resurgent Russia alignment—could be explosive.

In this context, it is useful to remember how Bismarck won an informal alliance with Russia by supporting Czar Alexander II against England and particularly France during an 1863 rebellion in Poland. Alexander II warned Napoleon III that continued French support for the insurrection would force him to abandon his alliance with France. Facing public pressure, Napoleon III ignored this warning. Seven years later, Prussia crushed France, Napoleon III lost power and a unified Germany was born—in no small part because Bismarck persuaded Alexander II to remain on the sidelines. China may not have a Bismarck, but Beijing could become increasingly bold in pursuing its geopolitical ambitions with tacit Russian support.

BY ALL appearances, Putin does not want (with or without Western sanctions) to invade Ukraine and accept the enormous costs of absorbing all or part of it even if some rhetoric clearly could be viewed as a threat to Kiev and encouragement to pro-Russian elements. Since the United States and European Union are likewise unprepared to fight to reverse the annexation of Crimea, the current standoff may remain under control for the time being. What we need to understand, however, is that Ukraine is today’s equivalent of both the Balkans and the Middle East of the Sykes-Picot era—an artificially divided land, assembled by Soviet Communist leaders on the basis of arbitrary borders. It includes people who speak different languages, have different religions, belong to different cultures and even civilizations, and have rather different aspirations.

The combination of contrasting historical narratives and an explosive political and demographic mix in Ukraine requires a lasting solution. This should include a unified federal Ukraine with meaningful autonomy for its regions and the right to select its own direction, though Kiev would not be able to enter NATO in the foreseeable future. With a modicum of goodwill and common sense, plus a genuine desire on all sides for a mutually acceptable solution, this is almost certainly within reach. The alternative is for Ukraine to lurch from one crisis to the next, never quite knowing exactly which specific event might trigger a full-scale confrontation between NATO and Russia in which military leaders on both sides would demand immediate and drastic measures to avoid being hit first.

One more look at the past is thus in order: Europeans were relieved when Austria’s 1908 annexation of Bosnia did not lead to war because Russia was still weak after its disastrous conflict with Japan and chose to retreat. New crises flared up in the Balkans over the next few years, but ended without general conflagration. Unfortunately, the brief periods between crises were misleading pauses in an ongoing struggle rather than times of peace. Like today, the forces at work extended far beyond the narrow disputes that erupted in the Balkans and elsewhere and few connected the dots—including to the second Morocco crisis in 1911, when Russia opted to support France after Paris promised loans that Berlin refused. As before World War I, there is much more than one point of friction that could produce a devastating conflict.

This drawn-out prelude to war gave Russia an opportunity to strengthen its military and build an alliance with its traditional nemesis, England. By the time of Austrian archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination in June 1914, the Russian Empire was prepared to stand its ground. The assassination was the catalyst for war, not the cause.

To the last moment, Nicholas II and Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm each thought that he could avoid war. When that moment came, however, Helmuth von Moltke, chief of Germany’s General Staff, persuaded the kaiser that Berlin had no choice but to order full and immediate mobilization—something Graham Allison recently described in The National Interest. Meanwhile, Russia’s military leaders persuaded a reluctant Nicholas II to take a similar decision, as otherwise the Germans—with their superior railroad network—could mobilize and attack first. As they say, the rest is history.

Dimitri K. Simes

---------------------------------------------------------------

Για περαιτέρω ιχνηλάτηση και πληρέστερη προοπτική

---------------------------------------------------------------

.~`~.