The classification of ideologies along the left-right continuum is in itself an ideological enterprise

Michael Freeden

*

Left and Right: The Great Dichotomy Revisited, Edited by João Cardoso Rosas and Ana Rita Ferreira This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by João Cardoso Rosas, Ana Rita Ferreira and contributors All rights for this book reserved. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5155-8, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5155-8

.~`~.

Left and Right: Critical Junctures

by João Cardoso Rosas and Ana Rita Ferreira

Left and Right: Critical Junctures

by João Cardoso Rosas and Ana Rita Ferreira

Introduction: a Short History

Anthropology and the Comparative Study of Religions have revealed that, before becoming “political”, the left-right divide was symbolically charged. Perhaps because of the structure of our brain and of the fact that most people are right-handed rather than left-handed, in many cultural contexts the right acquired a positive connotation and the left a negative one.

Often, the right was associated with cleanliness (the right hand performs clean tasks), whereas the left was related with dirtiness (the left hand performs dirty tasks). By the same token, the right was male, whereas the left was female, the right was good and the left was evil, the right was light, whereas the left was darkness. In short: the right was superior and the left inferior.

These connotations are also present in the religions that survived the modern world. Thus, for instance, in Buddhism the path to Paradise is bifurcated, but only the right-hand side leads to Nirvana. In Christianity, the Son is at the right-hand side of the Father and, in the Last Supper, the favourite of the Lord, the apostle John, is seated at His right, not at His left.

Our natural languages bear testimony to the historical and symbolic depth of these meanings. In English, if right means “to be right”, what remains is “what is left”. In French, “droite” means righteousness, whereas “gauche” amounts to clumsiness. In Italian, the “destra” is capable, whereas the “sinistra” is sinister.

The work of J. A. Laponce (1981) was fundamental in exploring these and other symbolic dimensions of the dichotomy, but also showed the political undertones of that duality before modern times. In the Ancien Régime, to be at the right of the king was better than to be at his left. But João Cardoso Rosas and Ana Rita Ferreira 3 other dichotomies, such as high and low, or close and distant, remained more significant than left and right. Laponce illustrates this point with the description of the French Estates General of 1789, just before the left-right dichotomy assumed its political dominance. In the opening session of the Estates General: “The king and his family, located at centre stage, under a monumental canopy, faced the deputies. The king sat on a throne raised on the highest platform. At the foot of the throne stood the king’s family: to the king’s left, the queen and the princesses – the female side of the royal house, which could not inherit the kingdom; to his right, the princes – the group of potential successors. At the foot of the central platform, lower than the princes and princesses who were themselves lower than the king, a long bench and a table accommodated the secretaries of state. The king, his family and his ministers were thus clearly separated from the members of the three estates who stood in rows ordered from right to left. The clergy was on the right side, the nobility on the left. The Third Estate, further removed from the king’s throne than either nobles or clergy, was linked to the two privileged orders.” (Laponce, 1981: 47).

Thus, until the end of the Old Regime, the up/down and the close/far dichotomies were still dominant. Verticality and distance were more significant than horizontal dispositions in the political space. Nevertheless, the left-right divide was already waiting in the wings, as it were, for the occasion to become the most relevant dichotomy in modern politics.

The modern re-invention of the distinction between left and right occurred when the representatives of the Third Estate decide to transform the Estates General into a National Assembly with a view to giving a Constitution to the kingdom, and were then joined by the representatives of the clergy and of the aristocracy. Under this new dispensation, which the king ended up accepting, the seats were no longer determined by rank. In a spontaneous way, the Third Estate together with some aristocrats and the low clergy occupied the seats on the left, whereas most aristocrats and the high clergy sat on the right.

It is clear that the spatial grouping in the French Assemblée Nationale had a practical purpose since the assembly was large and noisy and the deputies wanted to chat and to be close to the colleagues they identified with. But the fact that only a horizontal political space was available after the dissolution of the Estates General is very significant of this major turn in history. Moreover, while the decision about who should be seated on the left and on the right certainly reflected the deeper and historical meanings of left and right mentioned above, it also acquired more substantial content during the discussion of the rights of man and of the future of constitutional rules about the legislative veto of the king.

According to Marcel Gauchet (1992), who offers the most probing analysis of the evolution of this great dichotomy in French politics, it is the attachment to traditional religion and the powers of the king that distinguished the left from the right in a self-conscious way, from as early as 1789 onward. Nevertheless, Gauchet – in line with Laponce – notes that there are not only a right and a left, but also several different sensibilities, both on the left and the right. These different left and right “parties” changed over time, and with the accidents of the Revolution. Laponce believes that the extremes established the dichotomy, drawing a clear distinction between those who loved the king and of the Old Regime, on the one hand, and the partisans of democratic sovereignty and the republic, on the other hand. Gauchet points out that left and right are the product of a ménage à trois, since both need a centre and it is by reference to this centre that left and right are defined.

The clarification of the dichotomy and its internal distinctions occurs only later, during the first decades of the nineteenth century, and particularly within the framework of the Restoration, after 1815. Gauchet stresses the fact that, although the distinction had been established in 1789, its recurrence in popular opinion is a feature of the beginning of the 1820s. At this time, left and right represented the new and the old France, the liberals and the ultra-royalists. Many other configurations arose in the history of modern politics in France, but the memory of the Revolution and, in particular, of the Restoration, remained a strong point of reference for the distinction between left and right.

It goes without saying that the dichotomy extends, after the French example, to virtually all constitutional regimes and democracies in Europe and beyond, in the 19th and 20th centuries. The distinction is everywhere in the realm of democratic politics. Its pervasiveness is, in itself, a challenge to political reflection. One can understand the background and the historical origins of the political distinction, but its universality and resilience raise more questions: Why does democratic politics require a left and a right? Does this dichotomy have a substantive meaning? What does it mean in different empirical contexts? Is the distinction between left and right a useful instrument for the analysis of political ideologies? Finally, does the divide between left and right help to understand the current crisis in Europe? These are some of the issues that the use of left and right in political language poses for philosophers, political theorists and empirically-oriented political scientists. We will now say a bit more about each one of these critical junctures.

1. Left, Right, and Pluralism

Why do constitutional and democratic politics need a left and a right? An answer to this question probably revolves around the idea of pluralism. The acceptance of a pluralism of political outlooks and groups and, furthermore, its protection with the constitutional entrenchment of basic liberties, gives rise to the idea that there are several legitimate paths in politics, not just one. The left-right (and centre) distinction is a form of describing this pluralism.

If so, the political right needs the left, and the left needs the right (and both need the centre). This may be difficult to accept, since the work of politicians consists of explaining why the right is, indeed, right and that the left is wrong; or, conversely, that the left is right and the right is wrong. Understandably, politicians and doctrinaires attempt to occupy all the available political space and to expel their opponents from the playing field. However, without the right there would be no left; and in the absence of the left the right would make no sense.

We suppose this is what Steven Lukes (2003) refers to when he talks about “the principle of parity”. Lukes points out that the political vocabulary of right and left signifies a rejection of “pre-eminence or dominance” (Lukes, 2003: 608), and therefore an overcoming the symbolic and traditional superiority of the right over the left. In the modern “collective representations” of left and right “each has equal standing” (Lukes, 2003: 608). This is why many of those who reject the dichotomy are enemies of parity and, concomitantly, of democratic pluralism. They try to dis-identify with right or left and prefer to say “neither right, nor left” because they abhor competitive politics. It is for this reason that authoritarian or totalitarian politicians tend to present themselves as “beyond left and right”. This makes sense because they want to deny the relevance of pluralism, or perhaps to suppress it by force.

Nevertheless, not everyone who uses the language of “neither left nor right” want to deny the principle of parity. Some are defending a centrist view, or some form of middle ground (a third-way, for instance). In this case, they may still endorse the principle of parity. Others may want to un-identify with the left-right dichotomy because their own political camp is in a defensive position. Thus, for instance, in the southern-European states that made a transition from a right-wing authoritarian regime to democracy, when people say they are “neither left nor right”, this means they are “in the right”. By contrast, after the transition to democracy in the former communist countries of Eastern Europe, when someone said they were “neither right nor left”, this was because they were on the left. Again, in these cases people may be perfectly happy to accept the principle of parity, but they want to disguise the fact that they belong to one of two main political camps.

Although the connection between the great dichotomy and pluralist politics is unavoidable, it is also clear that left and right oversimplify “really existing” pluralism. It is often remarked – and rightly so – that there is not just one right but several; not just one left but many; not to mention a number of centres (centre-left, centre-right…). The literature on the subject agrees that this simplification plays an important role in pluralist politics. The pulverization of groups and outlooks makes it difficult for ordinary citizens to follow the stream of politics. The simplification provided by the left / right dichotomy therefore has a cognitive usefulness in that it reduces a plurality to a simple and more manageable alternative. In some cases at least, cognitive usefulness may come together with democratic usefulness. When the left is in power democratic citizens know they may turn to the right, and vice-versa. In this way, the dichotomy points to the existence of an alternative and helps to energize the political game. In other circumstances, however, the simplification may trivialize democratic politics, as when citizens end up believing that the alternation in power between left and right makes no significant difference.

2. The Problem of the Substantive Meaning

Thus far, we have highlighted the formal role of the dichotomy in pluralist politics, but have said nothing about the content of the distinction. Is “left and right” just an example of useful or convenient terminology? Has its meaning changed over time and space to the point of becoming meaningless? Or has it retained a core meaning that still applies universally and sheds light on the differences between those on the right and those on the left?

Norberto Bobbio is probably the main contributor to this debate (1999). His writings on the subject appeared in the context of an Italian debate that included scholars such as like Cofrancesco and Galeotti, among many others. However, unlike the work of his opponents and critics, Bobbio’s contribution has become influential beyond the Italian context.

Bobbio’s endeavour is analytic, not normative. He proposes to find a universally accepted criterion to distinguish between right and left. His argument is that the two sides of the dichotomy can be distinguished because of their different attitudes towards the value of “equality”. In a nutshell, the left tends to be more egalitarian than the right, on all occasions and in all contexts. This does not mean that the left is radically egalitarian, or that the right is never egalitarian. For instance, the liberal right may defend equality before the law, which is a form of equality. The left may oppose strict economic egalitarianism – indeed, this is usually the case in most versions of democratic socialism or social democracy – while remaining, by and large, egalitarian. The analytic criterion of “equality” suggests that, in every possible case and context, the left tends to be more egalitarian, and the right less so, but the distinction is a matter of degree rather than absolute or essentialist.

For Bobbio, the left is more egalitarian about the aspects to consider in the substantiation of equality. Take the example of access to healthcare. The right is more restrictive about equal access to healthcare, whereas the left stresses equality of access. This is why the those on the right readily admit that access to healthcare may depend on payments by the users of health services, whereas those on the left are more likely to believe that payment for such services introduces an unacceptable level of inequality.

The left also tends to be more egalitarian about the number of individuals to include in any given “equalizing” policy. For instance, when broadening the franchise is at stake – to, say, women in the past, or immigrants in the present – the left is likely to favour a wider set of criteria for who gets to vote, and the right will have a more restricted view. The left wants to include more people in the sphere of equality (in this case, in reference to political rights), whereas the right is more cautious about the inclusion of those who are outside the existing sphere of equality.

Finally, the left is still more egalitarian in the criteria it uses to defend equality. For example, the idea that “each should receive according to their need” is more egalitarian than the idea that “each should receive according to their merit”. Again, this does not mean that the right can never defend the former idea, or that the left will never uphold the latter. But it does mean that, when confronted with specific instantiations of these principles – for instance, the re-distribution of wealth – the left tends to follow the more and the right the less egalitarian view.

Steven Lukes, whose interest in the subject pre-dates the Italian debate about the substantive content of the distinction between left and right, says that the left is distinguishable from the right because it defends what he calls “the principle of rectification” (Lukes, 2003: 612). This idea is in line with Bobbio’s approach, but adds the point that the left is more, as it were, constructivist than the right. The right accepts the facts of inequality more easily, whereas the left points to them in order to rectify them. The left has developed social theories that unveil different aspects of inequality (in terms of wealth, opportunities, sex and gender, culture, age, etc.) and that focus on policy instruments to rectify them. By contrast, the right tends to criticize the excesses of the left in its project of rectification, often suggesting that they never produce the desired effects, and that they are utopian in the negative sense of the word. The dissatisfaction of the right with the rectification project of the left was captured by Albert Hirschman (1991) in his analysis of the “rhetoric of reaction”. For the right – and using Hirschman’s terminology – the rectification defended by the left is often “futile”, since it fails to produce the aims it wants to achieve. Moreover, the will to rectify the existing social order tends to generate what he calls “perverse effects” and “jeopardizes”. Instead of rectifying inequalities, the left very often ends up producing new inequalities, or, what is more, the demise of liberty.

The Bobbio/Lukes criterion – let us call it this – is not the only candidate for the distinction between left and right. Laponce (1981) favours a distinction based on the difference between atheism and religiosity, for instance. But while this distinction holds in many contexts, it will not in many others since the right may be atheist and the left profoundly religious. Another suggested distinction is between progressivism and conservatism. It is often assumed that the left is always progressive and the right always conservative. But this is certainly not the case. The left in Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall was conservative; and the liberal right that defended privatization and de-regulation in the eighties and nineties was progressive when compared with the status quo established by the post-war social-democratic consensus.

Another candidate for the distinction between left and right is the individualism/holism dichotomy. This point emerges in the Italian debate, but it was perhaps better articulated by Louis Dumont (v. Lukes, 2003), in the context of a debate about French national ideology. However, it is not the case that the left is invariably more individualistic and the right more holistic. Although that was the case in some contexts in France, the exact opposite may also happen. The left may be libertarian, but it quite often emphasizes the role of society, social class or social movement over the individual. The right is sometimes holistic, as in some forms of organic conservatism, but it may also be individualistic, to the point of declaring that “there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families” (Margaret Thatcher).

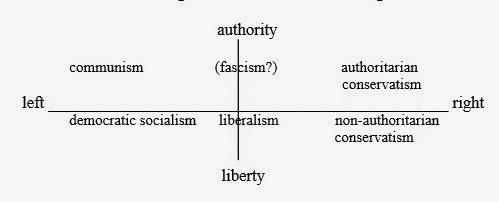

Still another candidate to account for the distinction between left and right is the liberty/authority dichotomy. However, as Bobbio remarks, liberty and authority are good criteria to distinguish between different lefts and different rights, but not between left and right. Accordingly, there are liberal and authoritarian lefts, but also liberal and authoritarian rights. This point is actually represented by the so-called bi-dimensional diagram, which is familiar to us because of the Political Compass test – an issue explored in greater detail below.

To sum up: the Bobbio/Lukes criterion seems quite operative and it is widely used by political theorists, in explicit or implicit forms. This is why many of the authors in this volume use it extensively. However, others may argue that it is too speculative and that it can be accused of essentialism.

3. Empirical Studies

Beyond the realm of Political Theory, empirical studies show that individuals tend to place themselves, parties and politics along a left-right spectrum according to the “equality criterion”. In fact, all around the world there seems to be a recurrent association between the left, egalitarianism and state intervention in society. By contrast, the right is invariably identified with market liberalization and lesser state intervention. This suggests that the empirical distinction between left and right is not far from the Bobbio/Lukes criterion.

First of all, it should be noted that when people are asked about their ideological positioning, they appear to be quite familiar with the lanaguge of left and right. The dichotomy clearly simplifies the complex world of politics (Fuchs and Klingemann, 1990), and an overwhelming majority of individuals has no difficulty defining their position on a spectrum that goes from extreme-left to extreme-right, passing through centre-left and centre-right. Indeed, empirical studies show that citizens employ the left-right dichotomy as the most important tool when they are thinking about politics, taking political positions and deciding about their vote (Knutsen, 1998). This means that “left” and “right” are not overlapped political resources. On the contrary, they still make sense for today’s citizens and, what is more, they structure the political competition – namely the party competition in European countries (Huber and Inglehart, 1995). The left-right dichotomy is still highly relevant in the empirical political world (Mair, 2007).

One could say that the mere fact that people regard these antithetical words as extremely relevant when making political decisions does not mean that they really understand the dichotomy’s substantial content. The left-right self-placement can be an elusive idea. However, empirical studies prove that citizens match their positions on the left-right spectrum with their level of egalitarianism and, concomitantly, their level of support for egalitarian policies. Individuals place themselves on some point along the spectrum in light of so-called socio-economic values. That is to say that those values play one of the most important roles in the identification of individuals as being either left or right – they are more relevant than moral values and post-materialist values in the ideological identification of each individual (Freire, 2006). These socio-economic values are truly connected with the idea of “equality”, since they call for different levels of social and economic equality and different ways to achieve them. So, it is largely one’s concept of equality that underlies one’s ideological self-placements.

Lipset and Rokkan (1970) undertook a historical analysis of modern political conflicts and presented four dichotomies that they claimed structured politics up until the 1970s: centre-periphery, church-state, rural-urban and owners-workers. The latter pairing, they held, was the most important one to understand politics, since social class was the most relevant factor in individuals’ ideological positioning and consequently in their party affiliation and vote. The owners-workers divide counterposed employees (those who work to earn a salary) against employers (those who own the means of production), an opposition that was reflected in the conflict between communist and socialist parties, on the one hand, and liberal and conservative parties, on the other. The former parties constituted the “left”, since they defended social and workers’ rights and state intervention to guarantee wealth redistribution, public social services, better living conditions and a reduction of inequalities. The latter parties made up the “right”, because they focused on the defence of free markets, with as little state intervention as possible, and were reluctant to accept any kind of measures of social or economic equalization (Freire, 2006: 101-102). This theory of historical cleavages – and particularly the social class cleavage – was the main approach to understanding ideological divisions, party systems and political competition in Western democracies until the end of 20th century, since citizens’ voting decisions were highly determined by their position in the social class structure. Empirical data showed that parties largely represented different social classes, such that workers were mainly leftwing and owners were mainly rightwing (Lipset and Rokkan, 1970).

However, in the 1970s, some other authors, notably Ronald Inglehart (1977), began to argue that new cleavages were emerging, which had the potential to challenge and even replace traditional social cleavages. Inglehart’s main idea was that societies living in peace, with strong social security networks and high levels of material well-being, would turn their attention from economic growth, safety and material security (materialist values) to other kinds of concerns, such as environmental protection and citizens’ participation in political decision-making processes (post-materialist values). He argued that while the former cleavages had structured political life in the past, the latter set of concerns would become highly relevant in individuals’ ideological positioning in conditions of security, prosperity and stability (Inglehart, 1977; Inglehart, 1990).

Other authors agreed the idea of a “new politics”, but preferred to talk about an authoritarian-libertarian cleavage rather than a materialist-post-materialist one (Kitschelt, 1994). This categorization suggested that libertarian principles – such as democratic participation, individual autonomy and social diversity – would shape the “new left”; and that authoritarian values – such as hierarchy reinforcement, limitations on individual autonomy and restrictions on social and cultural diversity – would shape the “new right”. Minorities’ rights and gender equality are good examples of the issues that characterize so-called “libertarian politics”.

In fact, there is a close connection between libertarian and post-materialist values. Both expressions hint at problems that are only powerful political issues in materially secure societies that can spare the energy to pay attention to other social questions. However, if it is true that traditional cleavages no longer determine individuals’ ideological positioning (Dalton, 1996), it is also the case that the new cleavages do not play a central role either (Gunther and Montero, 2001). Contrary to what Inglehart initially predicted, post-materialism (or Kitschelt’s libertarianism) did not win over social-economic topics in ideological self-placement. Social and economic questions have remained the major factor of political competition in old and new democracies alike (Huber and Inglehart, 1995). The redistribution of wealth, the economic role of the state, and measures that aim to equalize opportunities and outcomes (Freire, 2006: 65) are examples of social-economic topics that keep dividing left and right and have a clear impact on equality, even if they are not connected with strict social classes anymore.

It is true that in some European countries such as the Netherlands, France, Germany or Denmark, post-materialist issues are relevant for individuals’ ideological self-placement but they never explains more than 10 per cent of self-positioning. At the same time, in some of these countries, social-economic values remain the most relevant in explaining ideological self-placement: they explain more than 10 per cent of individuals’ positioning and, in Nordic countries like Sweden or Norway, almost 30 per cent (Freire, 2006, quoting European Social Survey 1999).

Post-materialism and libertarianism “have entered in the political agenda and created new bases of partisan conflict” (Dalton, 1996: 320). However, these new issues not only did not take social-economic priority, as they have also been absorbed by the left-right dichotomy (Freire, 2006: 119), since citizens on the left simultaneously show concern with social and economic topics as well as post-materialist-libertarian values (and the opposite happens on the right). In fact, questions raised by post-materialism and libertarianism can be easily set out in terms of more (or less) equality – even if they do not refer to traditional economic equality, but to new spheres of equality. For that reason, it is understandable that the (egalitarian) left has become sympathetic to those values and adopted some of them – while the (inegalitarian) right has maintained materialist and authoritarian positions.

Empirical studies prove that individuals who place themselves on the left are more likely to adhere to new rights for all citizens in order to ensure that all participate in political decision-making (rather than having political life overwhelmingly in the hands of a small elite), to extend rights to minority groups, reinforce women’s as well as environmental and quality of life rights, all of which means more equality among individuals. On the other end of the political spectrum, individuals tend to oppose “new politics’ demands” and focus on more materialist and authoritarian concerns – thus preventing a broadening of equality (Freire, 2006: 119-121). There is a match between the old dichotomy and (what has been thought of as being) the new one.

However, social-economic values have a stronger explanatory role than moral and post-materialist values in determining ideology. And, as expected, individuals who place themselves on the right defend a minimal role for the state in economic and social life and are less supportive of equalization through the Welfare State and redistribution. Individuals that consider themselves leftwing have the opposite attitude, defending state intervention in the economy, redistribution and the Welfare State as important means to combat inequality (Freire, 2006: 112-114). Although social class has ceased to be the major explanatory factor for ideological self-positioning, the old political topics are still relevant and still divide left from right. Grosso modo, there are more “right-wing workers” and “left-wing owners” today (an idea that would have seeemd rather absurd in the 1960s), but what determines the choice is still people’s attitude to equality among individuals.

It should be noted, however, that while social class is declining as a factor of ideological placement, “social identity” is becoming more relevant – and the latter depends on several aspects of social identification, associated with specific life styles, which may not be linked to people’s social origins. However, even this social identity (which includes trusting big companies or trade unions, or the frequency of religious practice) remains weak when it comes to explaining individuals’ positioning on a left-right spectrum (Freire, 2006), having yet to attain the explanatory power of social class.

Aside from values, there are other factors that contribute to the alignment of citizens on the left or the right. In most countries, party identification matters more than values. In fact, party dimension usually explains more than 25 per cent of ideological self-placement – and sometimes even more than 50 per cent (Freire, 2006). Nevertheless, since most political parties tend to identify with a specific chart of values and a particular ideology, this again suggests the relevance of the substantive content – and not just the form – of the dichotomy.

In short: empirical studies prove that the left-right dichotomy is still operative and makes sense in today’s politics. Further, they show that the dichotomy has retained its essential meaning, regardless of historical variables, and that no other pair of antithetical terms has replaced it, since none of the potential competitors sum up or clarify political life as comprehensively.

4. Left, Right, and Ideologies

Two aspects we have not dealt with directly thus far is the connection between left and right, on the one hand, and the language of political ideologies, on the other. The dichotomy “left and right” is part of ordinary usage in political language, but so is the vocabulary of ideology: socialist, liberal and conservative, among others. Is the left-right divide a useful instrument for the analysis of these and other ideologies?

The simplest way of answering this question consists in placing ideological outlooks along a line representing the spectrum from left to right:

left _______________________ right

However, there are several ways to organize this kind of representation, because the place occupied by ideologies has changed over time since the transition from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century (and as a result of changing societal contexts as well, of course). Very roughly, one may distinguish four different “ideological moments” in the history of Europe:

1) The first corresponds to the first decades the nineteenth century. In this context, liberals occupied the left end of the spectrum. They favoured reform, democracy, republicanism, anti-clericalism, the free market and a weaker state. Why should they be placed on the left? Because they were egalitarian given their opposition to the hierarchies inherited from the Old Regime that were based on blood and status (although they were not egalitarian as far as as private property was concerned). Conservaties took the right position. They were the party of order, tradition, monarchy, established religion, and favoured a stronger state. They occupied the right-wing end of the political spectrum because they were strongly anti-egalitarian, favouring inherited social hierarchies, even if they may have admitted the principle of “noblesse oblige”. Accordingly, the graphic representation for this period is as follows:

left _________________________________________ right

liberalism / conservatism

liberalism / conservatism

2) The second moment corresponds to a later period in the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, when socialist ideas and movements became increasingly important across Europe. In this context, socialists occupied the left end of the spectrum because they were more egalitarian than the liberals. Not only did they oppose inherited hierarchies, but they also favoured economic equality and opposed private property. By occupying the left-hand end of the spectrum, they pushed the liberals to the centre:

left _________________________________________ right

socialism / liberalism / conservatism

socialism / liberalism / conservatism

Interestingly, this re-composition never occurred in the United States, because socialist ideas and movements failed to gain popular support there. According to Seymour Martin Lipset and Gary Marks (2000), among others, socialism failed in the US because of deeply embedded historical and cultural factors (such as individualism). Whatever the reasons, the fact is that in the US liberals remained on the left and the conservatives on the right as in Europe at the beginning of the nineteenth century. This is not to say that U.S. liberals today think like European liberals did in the nineteenth century. The breaking point for American Liberalism was the New Deal. Since then, American liberals began to support a bigger state, whereas American conservatives, who first favoured a strong state, shifted to support a small state and laissez-faire economics. U.S. liberals should not be confused with European social democrats, although this is what U.S. conservatives think of them (hence their accusation that President Obama is a “socialist”).

3) The third moment in Europe waas the era of extremisms in the twentieth century. This period was particularly challenging for the left-right dichotomy as an instrument for the analysis of ideologies. Thus far, we have suggested that democratic ideologies may be placed along a left-right continuum. Another question is whether or not non-democratic or extra-constitutional ideologies can also be classified according to the left-right dichotomy. In Political Man (1960) and after, Lipset argued that the same yardstick should be used to analyse extremist parties and ideologies and their democratic counterparts, defining them as left, right or centre parties or ideologies. On the face of it, this would lead to the graphic representation below:

left _________________________________________ right

Communism / fascism

Communism / fascism

However, this is not the representation that Lipset’s observations suggest. He defends the counterintuitive thesis that classic fascism, or Nazi fascism, was not extremism of the right but rather of the centre. In purely ideological terms, fascism was similar to the democratic centre (or liberalism) in its opposition to big business, trade unions and the socialist state, as well as in its distaste for religion and traditionalism (although unlike liberalism, it also favoured a strong state). Moreover, the social bases of fascism are identical to those of liberalism: the middle-classes, small businessmen, white-collar workers and anticlerical professionals. Lipset argued that the rightwing extreme was occupied by authoritarian conservatives such as Salazar in Portugal and Franco in Spain; and that the extreme left was occupied not only by Communists but also by other egalitarian populisms such as Peronism in Argentina and other comparable movements in underdeveloped countries. Thus, a representation following Lipset would be as follows:

left ________________________________________________ right

Communism, Peronism, etc. / Nazi-fascism / Salazarism, Franquism, etc.

Communism, Peronism, etc. / Nazi-fascism / Salazarism, Franquism, etc.

Another way of representing the extremes departs from the traditional scheme and introduces a vertical axis, cutting across the left-right horizontal axis. This is the above-mentioned bi-dimensional representation that was popularized through the Political Compass tests. The second axis was first introduced by Hans Eysenk (1954), a political psychologist, to distinguish between democratic or liberty-inclined views, and authoritarian or authority inclined views. On this basis, one can place both democratic and non-democratic ideological outlooks in the same diagram, as follows:

There are reasons to be sceptical about the application of the left-right divide to extremist ideologies as suggested by Lipset and others. As shown in section 1 above, the dichotomy makes sense in a pluralist regime and it emerged with modern constitutionalism. A political continuum of extremisms is a counterfactual exercise of the imagination. In fact, there is no parliament of extremisms, no feasible coexistence between different extremist ideologies in the same political order. So the representation of extremisms as being on the left, right or centre is an attempt to find family resemblances between these ideologies and their democratic counterparts, but it does not tell us about the role of extremisms in politics.

Nonetheless, extremist ideologies arose in the framework of constitutional democracies and political pluralism and so they can be classified in accordance to their origins, even if they ended up denying the pluralist context from which they originated.

4) The fourth moment in the history of Europe covers the last two or three decades, in which both socialism and conservatism seem to have learned some lessons from liberalism. Although they maintain their respective positions on the spectrum, both conservatism and socialism seem to have incorporated liberal views. For instance traditional conservatism used to be suspicious of the radical forms of market liberalism, but this has not been the case at least since the 1980s and 1990s and the liberal-conservative synthesis initiated in the United Kingdom. Socialism used to be equally distant from economic liberalism, but this ceased to be the case after the emergence of the Third Way, or Die Neue Mitte, or similar shifts. If one excludes both the far-left and the far-right, in their democratic avatars, the representation of mainstream ideologies in the last decades of the twentieth century and of the beginning of the twenty-first might look like this:

left _________________________________________ right

liberal-socialism / liberal-conservatism

liberal-socialism / liberal-conservatism

Finally, does the analysis of ideologies from the point of view of left and right really help us to understand at least democratic ideologies? If one is to judge by the recurrent use of this frame of analysis in the literature, the answer must be yes. But there are sceptics too, particularly among those who study ideologies according to the framework developed by Michael Freeden, so-called “morphologic analysis” (Freeden, 1996).

According to Freeden and others, it makes little sense to represent ideologies along the left-right spectrum. The macro-ideologies – socialism, liberalism and conservatism – are deep and complex structures that interweave a number of concepts that have remained relatively stable over time despite contextual variations and interconnections. Macro and micro ideologies are not mutually exclusive and they do not always establish clear-cut alternatives for political action. Thus, the argument goes, ideologies do not exist in a continuum, as suggested by the application of the left-right dichotomy. There is no gradual ordering of ideologies, from left to right, or from more to less egalitarian.

Indeed, as Freeden argues, the classification of ideologies along the left-right continuum is in itself an ideological enterprise. It conveys the false idea that there is a fixed marketplace of political ideas, a set number of centrist, radical and extremist views that can be perceived easily and consciously by all. However, this is a simplification of what ideologies are about. Moreover, this simplification is induced by a behaviourist approach to politics, which focuses on concrete and well-defined forms of human conduct.

It should be noted that some of those who deny the relevance of the great dichotomy also deny the relevance of ideologies (although Freeden is not one of them). Typically, this happens when one of the sides of the ideological and political struggle is seen to have prevailed over the other. The idea of the “end of ideologies” was defended by Eduard Shills (1955) and Daniel Bell (1962) among others in the 1950s and 1960s, supposedly resulting from the defeat of fascism and the demise of Stalinism, and the future convergence of both sides of the Cold War in societies oriented to the satisfaction of consumers. At the end of the 1980s, Francis Fukuyama (1992) argued the even bolder case for “the end of history”, after the fall of the communist world in Eastern Europe, based on the belief that a single model of market liberalism and liberal democracy had definitively won the political battle.

The interesting point about theses that defend the end of ideology or history and deny the relevance of the left-right divide or of other political cleavages is that they have invariably been followed by powerful divisions and political struggles in the 1960s and in the first decade of the twenty first century, arguably pitting a left against a right and different ideological outlooks: the new social movements versus traditional society in the 1960s; and the opposition to financial globalization and deregulation versus the defence of free and open markets today.

So, it seems idle to deny the ongoing relevance of the left-right dichotomy even in the analysis of ideologies, although one should acknowledge that it does not always shed light on the diversity and complexity of the ideological world we inhabit (or that inhabits our minds). The left-right dichotomy, as stressed from the outset, is a simplification – perhaps even the greatest possible simplification – of the political alternatives available over time. It does say something about politics, but not everything that can be said about politics.

Final Remarks: Revisiting the Dichotomy in a Time of Crisis

This brings us to the critical juncture we face today regarding the theoretical and empirical relevance of the great dichotomy in the context of the crisis that began in 2007 or 2008 and is still unfolding, with particularly harsh consequences in Europe and in its periphery.

There are two competing narratives about what is happening, one clearly emanating from the left, another from the right. The first says that the crisis originated in the triumph of neo-liberalism in the 1980s and after the fall of the Berlin Wall, with the politics of privatization and de-regulation. The competing narrative sees the causes of the crisis in the intervention of the state in the United States housing market and thereafter with overspending by many states to avoid a deeper crisis.

There are also left and right solutions to the crisis, of course. The right believes that the solution lies in austerity for countries that face a debt crisis, whereas the left criticizes excessive austerity as counterproductive and advocates a more gradual adjustment. The left wants the state and the central banks – and the EU – to act in order to promote growth. The right emphasizes that growth can only come from sound public finances and market creativity.

Finally, there are expectations on the left and right regarding the aftermath of the crisis. The left believes that this historical moment is forcing us to re-clarify the divide along traditional lines. The issues at stake are social and economic, not cultural or symbolic as they were a few years ago. Thus, Europe and other parts of the world should return to the core values of equality and solidarity and defend the welfare state. For its part, the right believes that the left’s belief in a better future for the working classes is condemned to fail because of the limitations of economic growth and demographic change. Societies must become more efficient and sustainable, which is incompatible with the kind of welfare state and generous redistribution policies defended by the left.

Whether one thinks about the causes of the crisis, the solutions to the problems it has caused or about the expectations of its aftermath, one is unavoidably confronted with the great political dichotomy that has accompanied pluralist political regimes since they were institutionalized in the transition from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century. Must we think, once again, with and within that dichotomy, or can we think better outside it? The contributions to this volume provide answers to these and other questions in ways that are both theoretically sound and empirically informed.

.~`~.

Για περαιτέρω ιχνηλάτηση και πληρέστερη προοπτική

Για περαιτέρω ιχνηλάτηση και πληρέστερη προοπτική

*